We all want another Western Sydney Wanderers, but how can A-League expansion clubs get it right? The answer may be hidden within one of Europe’s most unusual teams.

Forget Bayern Munich, move over Borussia Dortmund. The hottest prospect in German football isn’t a superpower, it’s not even in the first division. Meet 2.Bundesliga’s FC St Pauli – ‘the alternative club’.

Founded in Hamburg in 1910, St. Pauli traditionally fell under the shadow of its cross-town rival Hamburger SV. A yo-yo club that nearly went bankrupt in 1979, until the mid 80s, Kiezkicker just couldn’t get it right.

But then something extraordinary happened that not only secured the long term security of the club, but gave it global relevance and an iconoclastic place in modern football - it became a cult.

If you’re thinking Charles Manson or Kool-Aid, think again. St. Pauli’s board struck gold when they began to rebrand the side around the unique characteristics of the club’s location – their area of Hamburg is located on the working class docks, home to the city’s infamous nightlife and red light district.

The area, originally named after New Testament apostle Saint Paul, now has one of the youngest, left wing demographics in Germany and a strong, progressive culture that far exceeds the notoriety of its ‘sinful mile’.

In the early 90s St. Pauli began to adopt a bold identity and a brash political ethos, rewriting the region’s football history in the process. In 1981, the club was struggling to pull crowds of 2,000. Since ‘91, they’ve been regularly selling out a 20,000 capacity arena in a district with a population of only 20,000 people.

What’s St. Pauli’s secret?

The German minnows had little to lose in 1985 when they attempted an outside-the-box solution to a run of the mill football problem.

The city was disinterested, spoiled by the success of rivals Hamburger SV, while St. Pauli’s failure to capitalise on brief periods of success had left them on the verge of insolvency.

At this vital stage, the board identified a passionate yet disaffected segment of the local population. They were then brave enough to take real action to garner their support - the key to avoid a pandering dynamic.

St. Pauli attracted an audience traditionally disassociated from German sport by embracing the punk movement early in official chants, songs and emblems (nowadays they’re more closely related to techno - they kept the fashion but lost the instruments).

But there’s substance behind St Pauli’s style - the club also focused on building a female audience - it now claims to be the best supported German football club among women - going as far as to remove advertisements for ‘sexist’ men’s magazines from within its stadium.

Punk, metal or techno heads aside, female audiences are a largely untapped segment of Australian football fans that no A-League club has been able to noticeably attract.

St. Pauli’s managed to cement a strong level of engagement among its target demographic through establishing a set of ‘Fundamental Principles’ - an almost biblical set of political and social aims that the club adheres to in all facets of operation.

Politics and sport, it’s enough to make a cautious club owner recoil in horror. But full-capacity average attendances don’t lie.

“St. Pauli FC is the club of a particular city district, and it is to this that it owes its identity,” the club’s statement of aims reads. “This gives it a social and political responsibility in relation to the district and the people who live there.

“St. Pauli aims to put across a certain feeling for life and symbolises sporting authenticity. This makes it possible for people to identify with the club independently of any sporting successes it may achieve.

"Essential features of the club that encourage this sense of identification are to be honoured, promoted and preserved."

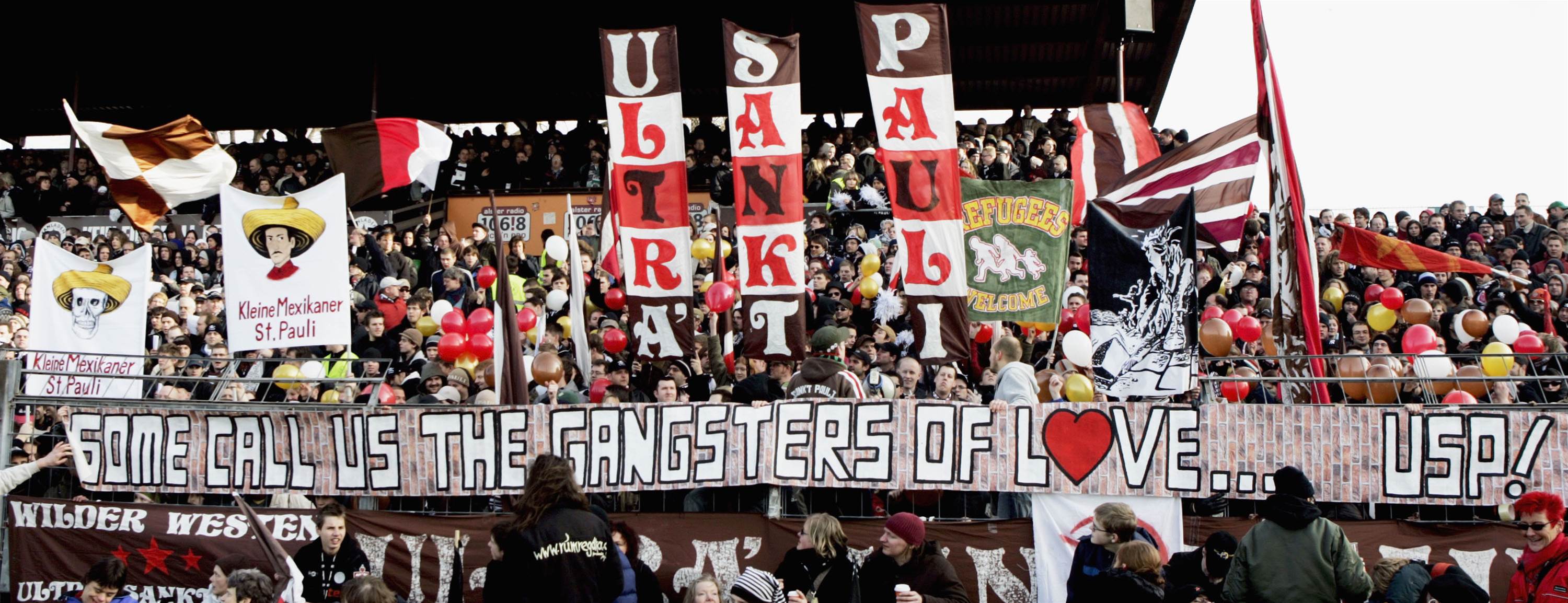

The club now has one of the most vocal active-supporter movements in Germany winning promotion to the Bundesliga in 2011 and building such a loyal fan base along the way that relegation in 2014 barely registered a blip on their support.

The obvious difference between Germany and Australia’s football culture - the tradition and dominant popularity of the sport - is one of the most interesting aspects of St. Pauli’s success. They’re a club that has managed, en masse, to recruit a formerly non-football audience by offering them more than just a game.

22-year-old Yasmin Rosenberg is not your average football fan. A peroxide blonde, tattooed, Berghain-regular chemistry student originally hailing from Malmo, Yasmin had never watched a football match before 2012, when she was led to St Pauli by a group of like-minded friends. Now, she’s a convert and regular 2.Bundesliga attendee.

“I became a fan because for me it is not only important how good, or let’s say how entertaining a club is, but also the things a club does outside a football game,” she said.

“If the club is political and in the same political wing, then how they act as a platform to spread important messages outside of football - like fighting for LGBT rights or helping with refugees - makes a huge difference.

Word of mouth and match-day experience become incredibly important for a club with a marginal existing supporter base, which is why Yasmin believes St. Pauli is a positive role model for A-League clubs to follow.

“I found out about St. Pauli from a friend of mine who was in the same political group as me when I was 14 or 15-years-old. He always wears their shirt so I googled the club and found out about the social programs St. Pauli were part of.

“I watched some games and slowly became involved. I actually attended my first match when I was 18 and ever since then I’ve been a diehard fan.”

The cliche that football is a way of life runs true in Germany - St. Pauli fans come from all walks of life, are based around the country and many barely watch other football teams. But come match day, they’re united in full voice; banners, chants and memberships galore, indistinguishable from the most passionate ultras in the world.

The club is now estimated to have 11 million fans just in Germany, despite never winning a national first division title and spending only eight years in the top flight in their 108-year history.

For Australia, a country where the proliferation of other sports minimises the capacity for football culture to move into the mainstream, taking inspiration from St. Pauli’s ability to attract a brand new audience and turn average people into ardent supporters sounds too good to be true.

Truth is, it takes some substantial risks.

Politics and sport

It takes guts to build a club’s identity around a certain political ethos and there are many arguments against sport becoming a playground for social activism - not least the propensity for crowd violence, which St. Pauli hasn’t been immune to.

Yet the club’s steadfast ideals; gender and racial equality, LGBT rights and investment in support for homelessness and low income workers are shared by the majority of mainstream Australia.

They’re also shared by many, if not all A-League clubs, which leads Yasmin to argue that perhaps, Aussie clubs just aren’t flaunting it enough.

“As long as the club’s activities are hyped, St. Pauli’s success could be replicated in a country like Australia,” she insisted.

“If a team clearly expresses what they want to do or on which political side they stand, they gather similar people around them. So it could work almost anywhere.

“The atmosphere at St.Pauli matches is amazing. I get tickets right where the hardcore fans are sitting because St. Pauli tries to make the ticket prices as low as possible so everyone can watch the game.

“So everyone is singing and cheering and it’s just a great experience. The main thing I love about attending matches is everyone becomes best friends for 90 minutes because the team unites us.

"I cheer and hug total strangers and it doesn’t feel odd in anyway, which is an experience hard to replicate outside of sport, so I have a lot of friends who have become big fans of St. Pauli, even though they aren’t particularly into football.”

What would an Australian St. Pauli look like?

This isn’t an opportunity unique to lefties and laté-sipping hipsters. Although the German trailblazers have pioneered a specific ethos, the possibilities for similar strategies are endless for existing and potential A-League franchises.

An expansion club has the lucrative ability to form this status from the ground up, but St. Pauli shows 70 years of pre-political existence matters little if the mind is willing and the board is able.

Team 11 - an expansion candidate based out of the Victorian suburb of Dandenong - are in a strong position to capitalise on this approach by actively engaging the cultural diversity of their supporter base, not just in words, but in action. Bids from Campbelltown and South Western Sydney tap into similar cultural hotbeds, while Brisbane City’s strong connection with the area’s Italian community offers it’s own opportunities.

There are 157 nationalities represented in Dandenong, with similar figures evident throughout Western and South-Western Sydney, largely united not by football, but by shared experience of immigration and living as an ‘outsider’.

A club that spoke directly to their needs and gave them a social voice, could attract a far larger and more loyal audience then some of the audiences that support other A-League clubs. The potential benefits, as evidenced by the turnaround popularity of St. Pauli, are lucrative.

Clubs like Brisbane Roar now face a problem of how to stabilise wildly varying average attendances - 18,000 when the team is winning, 8,000 when they’re struggling. It’s a misleading simplification to purely blame this on a fickle supporter base, but it’s relevant within the wider issue of inconsistent support across the league.

Wellington Phoenix also possess the chance - and like the Keizkicker, the desperation - to separate themselves from other New Zealand sporting sides by adopting a cause. It could be as simple as an Athletic Bilbao cantera approach towards Kiwi natives, or a more widespread, politically driven ideology.

Central Coast has the opportunity to drive rural values, hometown fervour and the rights of the disenfranchised small town community. Perth Glory, the endless struggle for West Australian independence.

It might sound churlish, but there’s little knowing what passions are bubbling beneath the surface of Australian regions before the opportunity arises for people to back something they really believe in. If Pauline Hanson and the sudden rise of One Nation aren’t evidence of this, it’s hard to say what is.

Working towards deeper meaning within our football clubs is a natural part of securing long-term support for the A-League.

There’s little evidence that this happens organically outside of countries with a widespread football culture - you only have to look at the dismal attendances across Eastern European competitions, which boast clubs of similar ages to the English Premier League or Bundesliga, to discern that success plays a far larger role in continued support than history.

So how to combat the curse of the capricious? St. Pauli may have provided our best answer yet.

Related Articles

Treble-winning Mariners enter ALM's greatest debate

Popovic expected to make call on Victory future

.jpg&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)