10 to watch in 2007

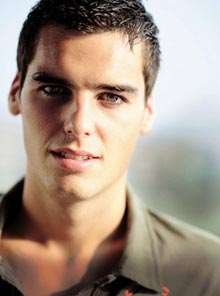

He’s the scar-faced winger with a turbulent past. And after setting the World Cup alight, he’s ready to bring his dazzling skills to England.

AGE 23

CLUB Marseille

POSITION Winger

LOWDOWN Fiery Frenchman who’s yet to settle at club level. Another move awaits.

Twelve months ago, not many football fans in Britain had heard of Franck Ribery. Hardly surprising, given that he was still playing in France’s Third Division in 2004. Back then nobody could have predicted he’d be one of France’s leading lights in an improbable run to the World Cup Final two years later. But now, aged 23, the boy who grew up on a rough council estate in the north of France dreaming of being the next Chris Waddle, has the world at his feet following a roller-coaster ride that has seen him first jump two divisions to France’s top flight, then scarper to Galatasaray for a six-month fling before returning to Marseille, setting Le Championnat alight with his trickery and joie de vivre, and forcing his way into the World Cup side alongside another of his boyhood heroes, Zinedine Zidane. As Ribery says: “It’s mad!”

And yet here we are predicting even greater things to come for the winger they call ‘Scarface’. Because the Ribery story, all Boy’s Own stuff with its unlikely twists and turns and rags-to-riches story arc, is set to continue on it’s upward climb. A host of big clubs are primed to pounce and Marseille are resigned to selling him to an overseas side to prevent him going to French champions Lyon.

Meanwhile Ribery, after a breakthrough 2005-06 season in France, where he won the Player of the Month award three times, was named Young Player of the Year and scored the Goal of the Season (a thumping 30-yard volley against Nantes), has shown that the better the level of competition, the better he plays. He got his first taste of the cream of world football in Germany last summer after his meteoric rise thrust him into Raymond Domenech’s France team and now Ribery wants more. Next season, he intends to be playing in the Champions League, and England should be the place he gets his chance.

“Franck is now a very big player in Europe and it’s true the biggest clubs want him,” says his representative, Bruno Heiderscheid. And, for once, we’re inclined to agree with an agent. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s go back to the start, to the grim northern port town of Boulogne-sur-Mer, where Franck Ribery was brought up and his problems began.

At the age of two, a horrific car crash saw little Franck go through a windscreen and pick up the scars down the side of his face that have marked him ever since.

“I was very young and I don’t remember what happened, but it was pretty serious,” explains Ribery, who has come to wear his disfiguration with a defiant form of pride after years of denigration.

“In fact, it’s not really the accident that has caused me the most problems as I was so young. It was more the way people looked at me. There were some who would take the mickey, and my family had to battle against that. I grew up with that. Now I’m earning a good living people often ask why I don’t have plastic surgery or something but I don’t feel the need. The scars are part of me, and people will just have to take me as I am.”

Like most of France’s working-class northerners, Ribery was brought up to speak the local patois, called ch’ti, a mixture of French and Flemish. And when he wasn’t at school or skiving, he’d spend his time at the foot of his dilapidated block of flats, kicking a ball around until dusk in the

notorious Chemin-Vert estate on the edge of Boulogne. It was there that he met his future wife, Wahiba, who persuaded him to convert to Islam. And it was playing for Boulogne’s youth team that he was spotted at the age of 13 and invited to attend the academy down the road at Lille.

It should have been the beginning of something good for Ribery, the ticket out of his dead-end town. Instead he ended up back in Boulogne three years later, kicked out of Lille for not trying in his school classes and getting into too many rucks.

“I got thrown out because I wasn’t very good at school, mainly,” says Ribery. He still remembers how he felt on hearing Lille’s decision: “It was frightening. I said to myself, ‘Maybe that’s it, maybe I’ll never be a footballer.’ The toughest thing of all was having to tell my dad that I wasn’t at Lille any more. My dad’s the one who counts the most for me as far as football is concerned, he’s always been there by my side. Luckily for me, I went back home and managed to play again straight away with the under-17s at Boulogne.”

Jean-Luc Vandamme, the man who whisked him off to Lille, refutes suggestions that Ribery is none too clever and prefers to explain the reasons he always believed the skinny youngster he first noticed 10 years ago could go on to make it to the top. “Franck has great anticipation,” Vandamme says. “He analyses three times faster than others. On the pitch, he has all the problems worked out while others are still pondering. People think he’s thick but that’s pure stupidity – he is anything but. He has a practical intelligence, like all the great players.”

As another early coach, Jose Pereira, says: “Even a street lamp would have been able to see that Franck was a very good player, but you always had to keep your eyes on him, like a pan of milk on the boil. He was a kid who grew up in the street.”

A teenage Ribery managed to work his way to Third Division side Alès, only to witness the club go bankrupt. Brest, in the same division, noticed though, and hoicked him off to Brittany in 2003. If we were just three years from the World Cup, Ribery was light years away from thinking he might be involved. But his season at Brest was to be a turning point. With the most assists in his division, the winger caught the eye of one of French football’s most respected coaches, Jean Fernandez, then at Metz. Several times Fernandez drove from Metz, across the north of France, to one of the country’s most westerly points to watch Ribery at Brest. He ended up getting his man. Ribery was 21 when he signed for Metz, then in the top flight, and they were his fourth club, not counting Lille.

“When we signed Franck he was ever so shy, and was coming out of a really tough period in his life where there were a lot of problems to deal with,” says Fernandez. “But he already had the qualities that he’s showing today, the same dribbling skills and great acceleration. At Metz, he became the man with the most assists in the six months he was with us. Today of course he has more recognition because he’s at a bigger club with Marseille, but everything that’s happening to him is no surprise to me.”

Ribery proved to be an immediate hit at Metz, drawing comparisons with the club’s favourite son, Robert Pires. He was called into the France Under-21 side after some impressive displays, coping with the leap up two divisions with few qualms. But then Ribery showed his impetuous side, quitting Metz after half a season for the unlikely destination of Galatasaray. French fans were stunned. Six months on they were stunned again when Ribery, who had proved a big hit with Galatasaray, even scoring in their cup final victory over arch-rivals Fenerbahce, announced he was returning to France to join up again with Fernandez, now at Marseille. There followed a legal wrangle with the Turkish club, accused of not paying the Frenchman’s wages, and a bizarre public spat with a former agent, who reportedly turned up on Ribery’s doorstep in Boulogne armed with a baseball bat in a bid to resolve one or two little problems between the two men.

Still, Ribery was excited at the thought of playing in front of Marseille’s impassioned crowds of 60,000 at the Velodrome, where his idol Waddle had once strutted his stuff and where Jean-Pierre Papin, another of his heroes, had banged in so many spectacular goals. And he was overjoyed to be back with Fernandez.

“His presence was fundamental in my development, he was the one who came to get me when I was playing for Brest in the Third Division, literally picking me up in his car and driving me to the other side of France to convince me to join Metz,” relates Ribery. “He was the one who got me in the top flight and he contacted me as soon as he was appointed Marseille manager. Jean Fernandez represents the greatest encounter I’ve ever had in football. He’s my spiritual father and I think he considers me a little bit like a son. He’s the type of man you never forget, and he’s also one of the best coaches in France. And he’s even crazier about football than I am!”

Ribery quickly conquered the hearts and minds of France’s most demanding and passionate supporters with his whole-hearted performances, mazy runs, dribbling skills and sheer will to win. He was hogging the limelight with his displays and there was soon a campaign to catapult Ribery into the national set-up for the World Cup. Domenech resisted and resisted, only to end up naming him even though he’d never picked him before. The uncapped youngster was in, ahead of Ludovic Giuly, Johan Micoud, Nicolas Anelka and Pires.

Ribery, who’d watched the manager name the squad live on TV like us mere mortals, celebrated with a kickabout in his garden with his brother. When asked to explain his late inclusion, he summed it up perfectly: “I think people wanted to see me picked because I’m the kind of guy who never cheats. I give everything I have in my guts when I’m out there on the field and then of course there’s my background, my story. What’s happened to me shows that anything can happen in football, that you can come from a long way down the ladder to realise your dreams. I think people like that idea too. Nobody thought I could do it.”

Do it, though, he did, working his way from an impact substitute in the pre-World Cup friendlies to a starting place in the tournament. And, despite a few teething troubles, when the competition really got going Ribery showed he was ready. Having struggled through the group stage, France were up against a Spain team that was firing on all cylinders and, for once, favourites to beat the stuttering French. The Spanish went ahead, only for Ribery to strike his first goal for Les Bleus, running through the opposition’s backline before firing in the effort that lifted French chins and ultimately launched them on their run to the final. A star was born.

Like everybody else in the French camp, Thierry Henry was under the spell: "Franck always shows this will to go forward, the will to attack," Henry said. “There are very few players in the world today who can accelerate like he does, brutally. He plays with freedom and he can unlock a match at any moment. He plays with his heart.”

Post-World Cup Ribery was again involved in transfer shenanigans, claiming to have contacts with Arsenal, where he dreams of playing alongside his new buddy Henry, before announcing live on the nation’s most-watched evening news bulletin that he would be joining Lyon. Marseille, still regretting the departure of Didier Drogba to Chelsea, were having none of it and Ribery stayed.

The fans wanted to give him a hard time for his apparent lack of fidelity, but Ribery carried on as if nothing had happened, tormenting visiting defenders and running himself into the ground – so much so that the supporters soon found themselves cheering him on again. Ribery wins over fans because he is one of them in much of his attitude and behaviour. He has qualities they want to see: he’s a winner who will always try to take people on, and who isn’t afraid to turn on a show when possible.

“I play how I feel: I don’t have a set way of playing as I’m an instinctive type of player,” he says. “When I get the ball I don’t hang around to think about it, I get going, and I look to create as much danger as possible. My greatest strength is simply the fact that I love football so much. I’m an attacking midfielder, not a forward, but I can play up front, on the left or the right. I even ended up last season playing just behind the strikers. One thing for sure is I won’t change the way I play. I do what I know best. I’ve always been guided by pleasure, whether in Division Three or in the World Cup, and I don’t see why I should change.

“For me, football is full-time. I live and breathe it. And when I see my dad, who works in the building trade, get up at 7am every day and finish at six in the evening, I say to myself that footballers are lucky.

“Even if I lack experience I have youth and spirit on my side. Pressure has no effect on me, I never feel it, and as soon as I’m out there I want to be taking people on and setting up people, taking chances. Sometimes I improvise and try dribbles I never even imagined. I’m always looking to enjoy myself on the pitch, that’s what I love! You have to give people value for money, and it’s in my character to give my all, to try everything, to make my runs, to go past people, to dribble with the ball, the kind of stuff that gets people off their seats.”

Stewards around Europe, you have been warned. Next season, as the Frenchman flies down the wings, you’ll be telling a lot of people to sit down. AC Milan’s tyro opted for backheels over backhands when he chose to play football rather than tennis. New balls please.

AGE 20

CLUB AC Milan

POSITION Midfielder

LOWDOWN He could have gone to Wimbledon... but only to play tennis

Yoann Gourcuff introduced himself to AC Milan’s fans in spectacular style earlier this season. Making his first start for the Italian giants since switching from Rennes a few months earlier, the 20-year-old Frenchman scored with a bullet header in his team’s 3-0 Champions League victory over AEK Athens. Although a relative unknown to most fans, Gourcuff’s transfer made ripples in France. Though the classy midfielder is expected to go on to great things, there was concern in his homeland that he might struggle to impose himself in Serie A. Gourcuff was having none of it.

“I really felt the time was right,” he explains earnestly. “I was ready for the challenge and where better to learn your trade, to take the next step forward, than at AC Milan?”

Gourcuff, whose father Christian is a former player and now manages French top-flight side Lorient, almost never became a footballer. Equally gifted at tennis, he only made up his mind a short while ago.

“I realised that it might be easier for me to make it in football,” he says.

It was the first of several difficult decisions he has faced in his fledgling career. After starting out at Lorient, where his father was in his first spell as manager, he had to decide in 2001 whether to follow papa to Rennes. Yoann initially wanted to join Nantes instead, causing his father to wonder what was going on and whether his son was as good as he believed he was.

To find out for sure, Christian asked Patrick Rampillon, head of the youth academy at Rennes, for his opinion. “I told him I would go to his house on my knees to pick Yoann up if it meant I could have him with me at Rennes,” Rampillon recalls with a grin. “He already had a great reputation.”

The young Gourcuff wouldn’t regret his choice. He scored in the final to help Rennes win France’s youth cup in 2003 and signed his first professional contract the same year, despite interest from Arsenal and Valencia. He made his first-team debut aged 17 and became a regular the following season, which he ended by helping France Under-19s to win the European Championships in Ireland, with Gourcuff scoring a hat-trick against Norway en route.

Gourcuff is neither a pure playmaker nor a defensive midfielder. His father sees him more in the role of a Fernando Redondo or an Andrea Pirlo. And at Milan, Gourcuff now has a chance to learn from the Italian World Cup winner.

Rampillon has no doubt his former protégé will become a major star. “You can tell that you’re looking at a top-class footballer, he has everything going for him,” says the man who guided ex-Arsenal striker Sylvain Wiltord through Rennes’ youth academy. “He has a natural authority, great vision, his play is fluid and he is very intelligent. He has a creative talent that you rarely see these days. He’s capable of making it right to the very top.”

When opponents say they’d prefer to mark his team-mate Romario, you know Nathan Burns must have talent. But the country boy is keeping his feet on the ground

AGE 18

CLUB Adelaide Utd

POSITION Striker

LOWDOWN A trip to Darwin as an 11-year-old focused Burns on success

Eleven-year-old Nathan Burns was a surprise selection for NSW primary schools at the National Schools Championships in 1999. It was unheard of that a kid from a small sheep farming town in country NSW could be picked ahead of one of the city players. But not only was Nathan good enough, it was there in the heat of Darwin that the sports-mad country kid had his own football epiphany.

“In Darwin, Nathan discovered all these other kids at the tournament had been on tours to places like Malaysia, Fiji and Europe. That’s what inspired him,” Nathan’s father Ray explains. “He told me when he came back from Darwin, ‘Dad, this is what I want to do.’ All Nathan wanted to do from that point on was to play with the best players possible.”

Burns returned to hometown Blayney (about five hours west of Sydney near Orange) with his football ambition burning bright. As Ray recalls, “it was pretty much full-time with his football from then on”. Nathan ditched the other sports he was excelling in – such as cricket and rugby league – and began training and playing football every day.

By 14, Burns’ reputation from western region representative football had filtered through to the NSW talent ID system. He was scouted by the NSW Institute of Sport (NSWIS) football program in Sydney, and the young striker had no hesitation in leaving his family and friends for the big smoke.

For the next few years Nathan was billeted out and trained like a full-timer: five days at Westfield Sports High (Harry Kewell attended the same school in the ’90s) and four nights a week with NSWIS. It toughened him up mentally, but having their son five hours drive away wasn’t easy for Ray and wife Denise.

“It was a fairly traumatic time,” recalls Ray. “We said if that’s what you want to do. And he said, ‘Dad if I don’t like it can I come home?’ I think his mum would’ve driven in the car that minute and picked him up if he had said he wanted to come home. Without that family support, we’d never have coped.” Their son certainly did cope though.

At 17 the striker was learning his craft with the best players of his age. He’d represented the Australian schoolboys and the Joeys in Peru 2005, and he’d been picked for the Australian Institute of Sport and Young Socceroos.

But a friendly for the Aussie U20s against New Zealand in May 2006 was Burns’ ticket to the next level: the A-League. John Kosmina signed the talented forward shortly after (apparently from under the noses of the rest of the A-League) and Burns has flourished under both Kosmina and Aurelio Vidmar’s tutelage, two of our national team’s best strikers over the last few decades.

He caught the eye on his A-League debut in August. Arriving as a sub, Burns energised a subdued United side in their opening day encounter at rivals Melbourne. In fact, he almost scored after having the confidence to run at the Victory defence.

Moving into 2007, Burns is now widely considered the most talented teenage striker in the A-League. His goals for the Young Socceroos in India – he scored twice against Thailand but also picked up a needless red card – and his three goals for Adelaide have placed him on the radar. Furthermore, he is currently training with Graham Arnold’s Olyroos ahead of the qualifiers for 2008 through Asia.

It’s not just the goals, but the manner in which he has delivered them. He’s comfortable on the ball, naturally quick and athletic and is a confident striker of the ball. Little wonder he’s been compared by some to the great Liverpool forward Kenny Dalglish.

“Yeah, I do pinch myself sometimes with all the opportunities I’m getting,” says the quietly spoken Burns of his ‘next big thing’ status. “The Asian Champions League is going to be unbelievable in 2007 for Adelaide United. It’s going to be a busy off-season next year hopefully with the U23s too.”

As for burnout (no pun intended), the teen admits that while the new year will be a challenge, he feels fresh after mainly coming off the bench at United this season. And at 18, you get the feeling he’ll be one of the more potent options for United as they trek through Asia in search of ACL glory in 2007.

One Burns fan is Alex Wilkinson. After the recent Central Coast match in Gosford, the Mariners defender said he was relieved to see Burns on the bench – some compliment given United had Romario in their starting XI.

Not that Burns himself is buying into the hype surrounding him. Despite eyeing off Holland, Spain (“it’s more technical”) and the EPL, he says, “I haven’t achieved everything yet… I’m still a long way off. Everyone has that goal to play for the Socceroos and I’m the same. I really just want to play well in the A-League in the next two seasons, then secure professional football overseas.”

“He has terrific support from the local community and the local players are very, very excited about Nathan,” says Ray. “He’s a great ambassador for the town. I’m an Aussie Rules man, so I don’t know that much about football, but it seems a lot of people are saying Nathan can go far.”

For the moment Burns is getting accustomed to being the centre of attention. He’s now looked up to back home (he spent a day back in Blayney after that Central Coast game and was mobbed by local players) and he hopes more kids will follow Adelaide and the A-League because, “there’s not much there [in Blayney]. “It’s been such a long journey since I started to where I am now,” adds Nathan, of his life since Darwin.

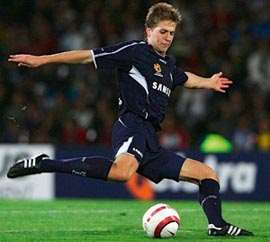

With his potential, that journey may have only just begun. By his own admission he lacks the class and clout of other foreign imports but pure hard work has taken the Premiership’s latest Dutch master a long way from his sleepy fishing village

AGE 26

CLUB Liverpool

POSITION Striker

LOWDOWN Has not looked back since being moved from wing to attack

Katwijk is a small fishing village on the west coast of Holland where the wind roars in from the North Sea, causing sandstorms on the beach and across the dunes. There is no railway station, but no need for one: the locals take the 10-kilometre bus journey to the nearest station or, if they get bored of waiting, walk. This is where Dirk Kuyt was born and grew up, where he began his football career, and where he learnt the qualities that look set to secure him hero status at Liverpool.

The 26-year-old is a rarity among Dutch footballers who have tried to succeed abroad: by his own admission, he lacks the technical ability of Dennis Bergkamp, Arjen Robben or Robin van Persie and the belligerence of, say, Edgar Davids or Clarence Seedorf. His strengths are much more English: physically powerful, rarely injured, with a unique desire to succeed.

“I grew up as a normal player, a striker who scores goals but also worked very hard,” Kuyt says. “I was the same as I am now only I practised more then. Even at an early age, my mentality was to work hard. Putting in a lot of effort has always come naturally.”

This is the Katwijk way: Kuyt’s father, Gerrit, was a fisherman who was out at sea for five days a week. The young Kuyt started playing for Katwijk’s amateur side, Quick Boys, when he was six. He soon rose through the youth teams and, when he was 10, his father gave him an ultimatum. “He said I must do the thing I liked the most,” says Kuyt, “and that if I was a fisherman, I wouldn’t be able to play football.” Kuyt chose football though, typically, thinks he would have been a good fisherman too.

That decision has been a blessing for the Liverpool fans, for whom Kuyt has proved one of few bright spots in a disappointing season. The Dutchman seems to have escaped Rafa Benitez’s rotation policy after scoring five goals in his first seven Premiership starts. In that period, he played alongside Craig Bellamy, Peter Crouch and on his own with Luis Garcia just behind him. He never complains, often smiles, and tracks back into his own area where he isn’t afraid to tackle hard. His willingness to chase lost causes comes from his experience as a winger at FC Utrecht, a period that also honed his awareness of space. “I play mostly behind the striker and because in England the teams hardly play with man-to-man defences but with zonal defences, it’s great to find the spaces to play in,” he beams. “I think my kind of play suits the English game really well.”

Tottenham coach Martin Jol calls him “a 20-20 player”, referring to his ability to score 20 goals and provide 20 assists a season. Benitez, meanwhile, has had to ask Kuyt to tone things down in training. “From the first day he was doing technical tests, I said to him, ‘Hey, you don’t need to run so much’,” the Spaniard says. “But he has always been a player with great stamina and he likes to work hard. He can play as a winger or a central striker. One of my former players even said that if I played him at full-back, he would still be one of my best players.”

Kuyt knows that his mentality gives him an edge over other players, and ever since he left Quick Boys and signed for Utrecht at 17, he has battled to prove himself. “It was my dream to be a professional footballer, though I was still very surprised when Utrecht moved for me.”

The teenager had not yet passed his driving test and used to get a lift into training at Utrecht with Alfons Groenendijk, briefly a Manchester City midfielder but also a Dutch league, cup and UEFA Cup winner with Ajax, and now assistant coach at the Amsterdam club. “Alfons used to tell me what it meant to be a professional footballer, and from that moment, I focused on improving myself in every area.”

Kuyt averaged eight goals a season as a winger at Utrecht, until his breakthrough in 2002-03. New coach Foeke Booy moved him up front and he responded with 20 goals in 34 matches. Kuyt also scored and was Man of the Match in that season’s Dutch Cup Final, a 4-1 win over Feyenoord.

A move to the beaten finalists followed, where he continued an incredible run of form and fitness that made the rest of Europe sit up and take notice. From March 2001 to April 2006, he played in 179 consecutive league matches. In peak physical condition, the boy from Katwijk was enjoying his new role. In his first term at Feyenoord, he scored 20 goals in 34 games. The following season it was 29 in 34. He made it four successive seasons topping 20 goals by notching 22 last season, when he was also club captain. To put that in perspective, the last Liverpool player to score 20 league goals in one season was Robbie Fowler in 1995-96.

“At all the clubs I played for, there was always the question, ‘Is he going make it?’ because I don’t have the talent of players like Thierry Henry or Robin van Persie,” he says. “But with a good mentality on and off the pitch – and especially on the training ground – I became better and better. At Utrecht and Feyenoord they still like me. The biggest compliment after I left both clubs was when someone said: ‘Don’t look for another Dirk Kuyt because there isn’t another player like him.’”

Similar questions about Kuyt’s qualities were raised when he joined Liverpool for in the region of $25m (£10m) last summer.

Kuyt had known that Benitez was interested in him the previous summer, but Liverpool had been unable to agree a fee with Feyenoord. “It was a difficult period for me as I had to start again in the Dutch league,” he admits. But at an international get-together soon after, Holland coach Marco van Basten took Kuyt to one side and said: “Relax. If Liverpool really want you, they will come back.” In August, when Kuyt was with the Dutch squad for a friendly against the Republic of Ireland, Liverpool did come back.

He received well-meaning advice, telling him to stay in Rotterdam and help his father Gerrit, who had been diagnosed with throat cancer. “He was seriously ill last year, and that was the period when I decided that I wanted to go to Liverpool,” Kuyt says. “I couldn’t do much to help him during his treatment and I knew how much he wanted to see me play for the team that we used to watch on TV at home.”

A frail Gerrit needed breathing apparatus when he gave Kuyt his Dutch Footballer of the Year trophy at an emotional ceremony in Hilversum in August. Three days later, he had an operation to remove his tumour. “Since then, the cancer has gone,” says Kuyt. “The doctors said it might be too malignant to heal so this seems to be a real miracle. He has to go to hospital every two months for check-ups, but it’s a big relief to us all.”

Gerrit watched his son for the first time at Anfield in the 3-1 win over Aston Villa in October. Kuyt scored Liverpool’s opener, and Gerrit will have seen the banner at the Kop End, reading ‘The Dutch Master’, in honour of his son.

England was always Kuyt’s likeliest destination, even though his early heroes were Marco van Basten and Ruud Gullit, then starring for Milan. Kuyt may have gone to sleep under a Van Basten duvet cover, but even then he was drawn to the English game. “The teams in southern Europe were popular when I grew up because of the Dutchmen at Milan and Barcelona,” he says. “But the mentality, the atmosphere and the way people live their football in England was unique and as I grew up, I felt that would suit me the best.”

Liverpool’s community spirit reminds Kuyt of his home town: they both have their own dialect and, although Kuyt’s English is excellent, he admits he is baffled when Steven Gerrard, Jamie Carragher and Robbie Fowler exchange Scouse banter. “It’s tough to understand them, but I like it when a city has its own dialect because the village I come from is the same.”

His compatriot Bolo Zenden was on hand with advice when he first moved, as was his neighbour and unlikely pal Craig Bellamy. “I really clicked with Craig and we used to drive into training together, but he has moved so I drive in on my own now.”

Kuyt has quickly grasped the importance of the city’s bond with the club. When he walked round an empty Anfield with his father, they both got goose-bumps down their neck. The Hillsborough tragedy, he thinks, has also brought the community closer. “Everyone needed to support everyone else during that sad time and it has made the players close to the city,” he says. “The club is big, but it’s also a big family. I feel at home here.”

Which may explain why Kuyt’s first five goals all came at Anfield. But it’s on the road where Liverpool fans really need to see his goal celebration – in which he kisses his wedding ring twice, in honour of his wife Gertrude and baby daughter Noelle – with five defeats in their first six away games all but putting Benitez’s men out of the title race.

“It’s going to be difficult,” Kuyt admits, “because we are way behind, but on the other hand, the Premier League is so tough that perhaps we can make a comeback.”

Kuyt is optimistic about improvements in his own game too. “I think I’m better than I was when I was at Feyenoord because of the level of my team-mates and of the competition here. In Holland there were teams that came to Feyenoord just to lose by a small margin but in England everyone goes out to win. Because of that, you need to be at your best.”

Not having the heavy burden of captaincy has also helped Kuyt in his pursuit of excellence. “I was the leader of the group at Feyenoord and because a lot of things went wrong on the pitch, I had to work, or at least felt obliged to work, extra hard to correct any mistakes. But at Liverpool you have so much quality with the players behind you that I can play and concentrate on my own game and that makes me better.”

With a decent supply line behind him – at home, at least – Kuyt has quickly established himself as Liverpool’s first-choice striker and it is a four-way battle between Bellamy, Crouch, Fowler and Garcia to play alongside him.

“I was not afraid of the challenge,” he says, “but I knew that the tough competition for places would make me stronger. Now I feel that I will always play when I’m fit.”

If that continues, few would bet against Kuyt producing another ‘20-20’ season. But despite now plying his trade for a genuine European giant, Kuyt will never forget his roots. He still returns to Katwijk whenever he can and is always a welcome spectator at Quick Boys, who netted a more than useful £300,000 from his move to Liverpool. His contract at Anfield runs for another four years, by which time he’ll be 30 – too soon, perhaps for him to return to where it all began. But he already has one eye on home.

“I only started one game in the senior team for Quick Boys and I didn’t score for them, so I’m still waiting to break my duck for the local side,” he grins. “I want to go back to playing for them when I stop as a professional, so maybe one day I will score for them.”

For now though, he’s busy enough with the responsibility of scoring the goals that Liverpool fans hope will bring the title back to Anfield for the first time since 1990.

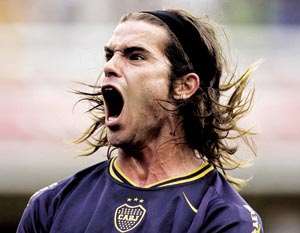

Having single-handedly reversed the fortunes of Boca Juniors, the new Fernando Redondo sets his sights on conquering Europe with Real Madrid

AGE 20

CLUB Boca Juniors

POSITION Midfielder

LOWDOWN His grace and grit could revolutionise Real Madrid’s midfield

“Just as in the desert you can find a flower, in the histrionic league of Argentina has appeared a boy that thinks fast, passes quick and wants to play all the time. That is a blessing. Indeed, a miracle,” says Jorge Valdano. The player he speaks of is Fernando Gago. And from the moment he first wore a Boca Juniors first-team shirt as an 18-year-old in December 2004, it was obvious that the Buenos Aires giants had not only unearthed a natural-born footballer, but a natural-born leader too.

Just as the young Academy lad John Terry snapped fearlessly at senior Chelsea players, Gago barked out orders as though he was a seasoned Boca professional, caring not if his gestures were directed at fragile youngsters or players 15 years his senior.

Rather than crumbling under the pressure of coming into a crisis-hit team who played dull football, the young central midfielder ensured his new team-mates played to his tune. Short passes and constant movement, with the ball delivered to feet, were enough to transform Boca into a different team, almost overnight. Magazine El Grafico explained that the difference with Gago on the pitch was as obvious as watching a film on a small, portable TV and switching to a home cinema with Dolby surround sound.

Playing with such elegance and authority, Gago quickly gained the respect of his team-mates, while neutral observers hailed the emergence of Argentina’s most gifted No. 5 (as holding central midfielders are known in Argentina) since Fernando Redondo. Among those observers was Redondo himself.

“I used to imitate Redondo’s movements and the things that I always liked about him were his elegance, how he defended and how he always offered the team a solution,” explains Gago. “And it was a real surprise to me when I read that he was praising me about these same qualities. I mean, it was the footballer from my posters speaking about me!”

Unlike his idol, Gago is predominantly right-footed, but the similarities aren’t lost on anyone. “That kid plays as though he has his neck broken, it’s incredible. He never looks down,” says Alfio Basile, Gago’s Boca coach who’s now back in Argentina’s hot seat. “He will be the axis around which the future Argentina will be built. I’ve managed Redondo in 1994 and Gago at Boca; the resemblance is incredible. With Gago, a team can play smoother, simpler and quicker.”

Typically, Diego Maradona had his say too: “Only the five biggest clubs in the world are in his category.” As FourFourTwo goes to press, two of those clubs, Real Madrid and Barcelona, are vying for Gago’s signature, with a $30m price tag mooted and Gago said to prefer the capital club. Boca president Mauricio Macri admits the club will be forced to sell once the current European season ends. ‘The Little Prince’ says he would prefer to play in Spain, rather than Italy or England, yet it’s a current Serie A star who learnt his trade in the Premiership who Gago most admires in today’s game. “Patrick Vieira has a physical presence that is stunning,” he says. “And he is very good at attacking, not just sitting back or covering gaps. I love the way he plays. [Andrea] Pirlo is very good, too, but you can see he originally was an attacking midfielder. He doesn’t mark so much.”

Defending is an art that often goes unnoticed in Gago’s game, but playing for a club who celebrate a tackle as much as a nutmeg, he quickly set about convincing the fans that he didn’t mind getting his shorts dirty. Thankfully, he’d already had plenty of practice. “I used to be the anchorman in a 4-3-3 formation for the Boca academy team and I had to mark the opposition’s No. 10.”

But it’s in possession of the ball that he really excels. Maradona described Gago’s style as that of a windscreen wiper, swinging the ball left and right, constantly on the move. When he receives the ball again, as is often the case, he is invariably free of markers, though not for want of trying on the opposition’s part. “At the beginning I was shocked to see that I had one or two players following me closely, because I’m not a No. 10,” he says, “but it’s all a matter of having patience and finding the gaps. If there are two players close to me, then there’s got to be space elsewhere.”

And invariably, Fernando Gago will find it, as European audiences will discover from next season. Meet the direct, pacy winger who suffers panic attacks in public. Good job his table-topping team are rarely on the telly, then

AGE 21

CLUB Sevilla

POSITION Winger

LOWDOWN Assists, pace and delivery make him Spain’s next big thing

He may have only just turned 21 but Jesus Navas has already won the UEFA Cup, been a regular in the Sevilla first team for two seasons, and racked up over 100 games for the leaders of La Liga – statistically the best club in the world. He has been described by the country’s best-selling newspaper as a “superstar who is the heart and soul of Sevilla”, the man whose “electric play and wonderful assists on the right wing fill the Sanchez Pizjuan week after week.”

And still football fans could be forgiven for knowing little about him. After all, beyond Real Madrid and Barcelona, the rest of Spain’s clubs struggle to get noticed by many people and Sevilla are not in the Champions League, having missed out on goal difference last season. As for Navas, he has not been on television, he barely does interviews and has not yet played for Spain. In Seville, he’s been talked about for years; outside the city, he has yet to take the stage his special talent deserves.

Short and slight with a boyish look and piercing blue eyes, like the rest of his team-mates Navas went unwatched this season as Sevilla took the league by storm and their president took the television companies by the balls, insisting that no cameras would enter the Pizjuan until the offers improved dramatically. “It was a shame,” Navas says softly, almost imperceptibly, when FourFourTwo meets him in the pouring rain at the club’s training ground out on the Utrera road. “Because we were playing pretty well and hardly anyone got to see us.”

Pretty well? That’s an understatement and a half. With the cameras banned, Sevilla put opponents to the sword in devastating, swashbuckling style. By the time a TV deal was struck and the cameras finally returned, they had overthrown Barcelona at the top, with Navas their star man, tearing up and down the wing at the speed of light, providing assist after assist.

Long considered to be the new improved Jose Antonio Reyes, the Andalucian artist, an old-fashioned winger, Navas joined Sevilla at 13 and was destined for the top. The pair are best friends and Navas admits that he sees himself in the Reyes mould. “My style is his style,” he says, “it’s about pace, running at people, wanting the ball. It’s very direct – the kind of football people love here in Andalucia.”

Except that Navas is better than Reyes. Pablo Blanco is the ex-player running Sevilla’s youth system, a man who knows about talent. “Navas’s football is the very embodiment of exquisite finery: he has enormous ability and great variety,” he says. “Some say he has a physical weakness, but that just makes him even more of a footballer, in pure form – like Johan Cruyff. He has great mental strength and the pace, talent and bravery to go at people again and again. He will triumph.”

Even so, when then coach Joaquin Caparros put Navas in the first team in November 2003, some considered it a gamble. Not Caparros. “Players make first-team debuts for one simple reason: they are good enough,” he said. “I like to bet on a winning horse. And anyone would bet on Jesus Navas.”

Caparros’s successor, Juande Ramos, certainly would. Indeed, the arrival of Ramos has heralded a more creative style – one Navas admits “suits” him – that has brought the very best out of the youngster. “With so few out-and-out wingers around, having Jesus is fantastic for the team,” Ramos insists. “He will always beat his marker, giving us a real advantage.”

“He may look like a little boy but he’s so, so dangerous,” adds Denmark international Christian Poulsen, who joined Sevilla in the summer. “He’s very good technically and he’s incredibly quick; Navas could be a star in Spain and well beyond.”

Yet still Navas has not played for Spain, despite coach Luis Aragones proclaiming he is destined to be “one of the biggest footballers in the country”. Aragones has wanted Navas in the squad for a long time but has been unable to select him because the winger suffers from serious anxiety attacks, even having to leave one Spanish U21 get-together because he couldn’t cope.

Sevilla, who asked Aragones not to pick Navas, are helping the winger get over those attacks by providing him with treatment and counselling. He does not travel with the team on long trips away, instead joining them just in time for the games, and slowly but surely he is making progress.

With an international call-up now expected next spring – possibly even for the friendly against England at Old Trafford in February – 2007 is pencilled in as the year Navas announces his arrival. And when he does, rest assured, he will do so in style.

“He’s in the process of overcoming the problems that have prevented him being one of the best players in the world already,” says Ramos. “And as soon as he has the chance to establish himself amongst the elite, people will see him for the fantastic talent he is. It’s just a matter of time before the rest of the world discovers what people in Spain already know: that this kid is a superstar.”

It’s just one of a catalogue of eulogies, but is Navas really as good as they say? “No,” says Freddie Kanoute, smiling as he shelters from the rain. “He’s better.” Barcelona’s latest rising star walks like Ronaldinho, plays like Ronaldinho and shares the same outrageous ball skills. No wonder the Brazilian names young ‘Gio’ as his successor

AGE 17

CLUB Barcelona

POSITION Midfielder

LOWDOWN Moved to the Nou Camp at 13 then shone at the U17 World Cup

Three years after staging a 1986 World Cup game where eventual Golden Boot winner Gary Lineker scored a hat-trick against Poland, the wealthy Mexican city of Monterrey welcomed Giovanni dos Santos Ramirez into the world. Football was in his blood; the only reason he was born in Mexico was because his Brazil father Gerardo – or ‘Zizinho’ – was a playmaker at CF Monterrey.

Now 17, Dos Santos is the most talked about young footballer in Barcelona since Lionel Messi. Like the precocious Argentinian, he moved to the club at the age of 13, along with his family, after being spotted playing in a youth tournament in France for San Paulo of Monterrey. Not only was he the tournament’s top goalscorer, but the variety of goals and range of his passing astounded scouts.

Dos Santos – and his younger brother Jonathan – moved quietly through the system at Barça. And then he starred in the FIFA Under-17 World Championships in 2005, leading Mexico to a 3-0 final victory over Brazil in Peru. ‘Gio’ – as he likes to be called – was brilliant, runner-up for the competition’s Ballon D’Or and heralded by the Spanish media as the next star to rise from the fertile Barcelona youth ranks that have nurtured Cesc Fabregas and Messi.

Ironically, that success created a problem for Barça. Unlike English clubs, they can only legally offer a player a professional contract when he is 18. Stung when Arsenal snared Fabregas and Manchester United grabbed Gerard Pique, the Catalan giants were determined to prevent the same thing happening with Dos Santos. The club therefore set up a trust fund for him and his brother which covers educational fees and the rent of the family apartment until he is 20. It didn’t stop Chelsea and Manchester United, plus Mexican sides Club America and Monterrey, making doomed overtures.

Last season the English champions went directly to the player’s father, who acts as his agent, and told him that they had been following Gio’s progress and were prepared to offer him a professional contract. “We said no because nothing was going to destabilise my son at a point when he was deeply involved in trying to win the World [Youth] Cup for Mexico,” explains father Gerardo. His mother, Liliana, adds: “We have received many offers, but we have an allegiance to Barcelona because we think they are best for our sons.”

Dos Santos’s explosion into the Catalan public consciousness didn’t come until the summer of 2006 when he was promoted to Barça’s first team for an exhaustive pre-season schedule which included games in Mexico and the United States. He was a revelation, scoring a wonder goal when he skipped past two defenders on the right of the box before lashing the ball into the far corner of the net from an acute angle.

Comparisons with Ronaldinho were immediate and inevitable. They walk the same walk, possess a similar burst of pace and the same wonderful ability to elude challenges. “These comparisons will always exist in football,” explains Dos Santos. “I am grateful to be compared to Ronaldinho, but I am a player who has barely begun his career and has everything to prove. I am learning a lot, but I am aware that the most important thing is the team and not the individual. They all tell me to take things calmly and that I should do what I can. This is advice I will always remember.”

Dos Santos may not thank him for it, but asked by FourFourTwo to pick the next Ronaldinho from all the players in the world, the real thing chooses his teenage club-mate. “He can give the team a new dimension,” the world’s best player insists. “When he trained with us, he felt comfortable and he has a lot of quality. I’d like him to play with us.”

Dos Santos certainly has his sights set on the first team. “Lionel Messi has opened the door. He has shown that players from the youth teams at Barça can play for the first team if they are good enough. Lots of us want to follow him.” At the age of 20, Messi finds himself cast as an unwitting father figure, apparently dispensing advice to the young Mexican.

This season has not all gone to plan for Dos Santos, however. While the Barca B team for which Messi played pushed for promotion to Spain’s second division, the current team has won just one of their first 12 games after losing three experienced players in the summer. Injury has prevented Dos Santos featuring in that miserable run and, while Barça have registered him in their squad to defend the Champions League, regulations block his way to the first team for league games. Spanish clubs are only allowed to play three non-EU players (though many of their ‘foreign’ stars have EU passports). At present, Barça’s overseas representatives are Ronaldinho, Samuel Eto’o and Mexico captain Rafael Marquez, who is due to receive a Spanish passport in January. Having been in Spain for almost five years, Dos Santos has applied for a Spanish passport too. As soon as he or Marquez get their papers, Dos Santos can play.

Alex Garcia, his coach at Barcelona last season, is convinced he’ll be a success. “He is a normal, attentive boy in the changing room, someone who seems content with life. On the field he is explosive, like Lionel Messi. He has superb technique, accelerates quickly and has the ability to stop and change direction just as quickly to confuse opponents. It’s very hard to knock him off the ball because physically he is so strong. He is a goalscorer at the moment, but in time I think he will become more of a playmaker. I think he’ll play in the first team soon. A lot of things will depend on him making the first team, but he has the qualities to play alongside the best players at Barça.”

As for his international aspirations: “My son is already ready to play in the senior Mexico team,” says his father. “And even though I am Brazilian, I wouldn’t be opposed to him choosing to play for Mexico because of the great affection that everyone in my family has for Mexico.”

Get ready for a Mexican wave. America’s first gangsta-rapping footballer is looking for a move to English football. And the man they call “Deuce” is bringing his hip-hop celebrations

AGE 23

CLUB New England Revolution

POSITION Midfielder

LOWDOWN Bad boy Texan set for a move to the English Premiership

Like many things American, Clint Drew Dempsey – aka “Deuce” – can be loud, proud and in your face. But unlike some of his US contemporaries, this son of a trailer park from Nacogdoches, Texas, looks set to be a big hit in the Premiership.

Certain wannbes might ape gangsta, but from his ghetto roots to the tragedy that has tinged his battle to emerge successful, Deuce is the real deal. A skilled rapper, he featured in Nike’s “Don’t Tread” campaign, but suffered heartache when, just before the World Cup last summer, his rap partner Big Hawk was gunned down on his way to play dominoes at a friend’s house. (It’s not the only sorrow he’s suffered: as a teenager his sister Jennifer, a talented tennis player, suddenly died from a brain aneurysm.)

Yes, Deuce is a far cry from the soccer moms and leafy suburbs that is the breeding ground for the MLS. He represents a rare breed of US player that will, over time, become its mainstay: hungry, working-class heroes with a point to prove.

Growing up in Nacogdoches’ predominantly Spanish community he learnt his trade in their men’s leagues playing with retired pros. “They taught me a lot,” he says. “It was sink or swim. As a youngster, it forced me to grow up and be tough because they weren’t there to do me favours.”

South American football inspired Dempsey to take up the sport and his hip-hop celebrations. “Growing up seeing teams like Argentina attracted me to soccer. I watched them score and they’d go crazy. That made me realise that football is about being yourself; I wanted to do the same.”

At the World Cup Dempsey got a chance to bust a move in front of a global TV audience when he equalised against Ghana. “For that celebration I used the Heel-Toe from a Sean Paul video,” he says, “and recently I popped my collar against DC United.” He has also marked goals by imitating a baseball player, a fisherman and Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, as well as jumping into the crowd to kiss his mum.

No wonder: Dempsey’s family made huge sacrifices just to get young Clint (named after Mr Eastwood – his dad’s a huge fan) to training. Dempsey’s youth coach Hassan Nazari recalls his mother revealing that her son would love to play for the Dallas Texans. “She had a six-hour round trip to training. It must have been hell. But they’re very close-knit and he always appreciated what his mother did.

“He’s clever, has great athleticism and tremendous technique. It was also the way he thought on the field that impressed me. He reminded me of Luigi Riva from the World Cup in 1970 for Italy.”

Yet for all the positives, Dempsey has also gained a reputation for the darker side of his character. Three times this season he’s been suspended for violent conduct, though he claims to be “competitive” rather than aggressive. “I’m no martial artist or anything like that,” he says, “but I do like Bruce Lee movies. Growing up a country boy, I’ve been in a few scraps in my day.” He can take knocks, too: he played on for a fortnight with an undiagnosed broken jaw.His New England coach, Liverpool legend Steve Nicol, is quick to defend him: “His quality causes the opposition to look out for him. He’s just trying to protect himself.” Perhaps it’s that edge that propelled him from 2004 MLS Young Player of the Year in his first season to Nike endorsements and the World Cup two years later.

Dempsey’s performances there caught Europe’s attention, but the MLS blocked a $1.5m move to Charlton, feeling he was under-valued. “It didn’t make sense to me,” he says. “I was getting paid under six figures and yet they wanted to charge over seven.”

The attacking midfielder now has offers from “three mid-table clubs” and says he expects to move to England in the transfer window. Nicol predicts big things: “Clint uses both feet, gets in the box, and has a really soft touch. He sees thing early. The boy can play.” Korea’s next export is a multi-faceted midfield marvel – and he’ll say so himself

AGE 25

CLUB Ulsan Hyundai Horang-I

POSITION Winger

LOWDOWN Too good for Korea’s K-League – and he knows it

There’s a saying on the Korean peninsula that the most handsome men can be found in the South while the prettiest women live in the North. Yet in fact it is South Korean women who are famed for their beauty while a Brazilian website voted Lee Chun-Soo the ugliest player at Germany 2006.

Strange hair colours aside, this seemed harsh, and Lee’s style of play, at least, could be described as anything but ugly. Widely regarded as South Korea’s best player at the tournament, Lee scored their first goal too, a trademark free-kick to level the scores against Togo. And, along with Celtic’s Japanese playmaker and our own Timmy Cahill, Lee is probably Asia’s finest footballer.

“He’s got everything,” says South Korea coach Pim Verbeek. “He can play on the left or right, is fantastic at free-kicks, works hard and has a great mentality. There is no reason for any coach not to like him.” Or, as one Argentine journalist remarked in Germany: “He is smart and understands the game. He’s very expressive; he doesn’t look like an Asian player.”

He doesn’t behave like a typical Asian player, either, at least not a typical South Korean player in the Park Ji-Sung, Seol Ki-Hyeon or Lee Young-Pyo mould. Opinionated, brash and flash, the 25-year-old winger counts pop stars and movie stars among his friends and is a regular in South Korea’s gossip columns. He is also no stranger to controversy...

He was not the only South Korean player to write a book about the 2002 World Cup but was alone in saying unflattering things about team-mates and coach Guus Hiddink. His comments were not well received and soon after, he was booed by fans throughout the K-League All-Star game.

Having just been carpeted by the South Korean FA for giving the finger to opposing fans at a match, a move to Spain came at a good time. And although he was ultimately unsuccessful during spells with Real Sociedad and Numancia between 2003 and 2005, the experience made Lee a more rounded player.

Upon his return from Spain in July 2005, he inspired Ulsan Hyundai Horang-I to the K-League title and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player in December 2005 – despite the fact that he only played for half of the season.

After rising above South Korea’s general mediocrity at the World Cup in Germany, a move to England beckoned for the 67-times-capped winger. “Four teams are interested,” said Lee, modestly. “They may not be as famous as Manchester United but they are medium-level clubs.”

Lee obviously knows his Premiership, as three of those four were reportedly Manchester City, Aston Villa and Portsmouth, with only the latter making a concrete offer. The Incheon-born star said no, instead deciding to wait for the “perfect offer” in the January transfer window, one that doesn’t involve a trial or a loan.

In the meantime, Lee’s stock continues to rise. He was unplayable in August’s East Asian Champions Cup in Japan. Against the Chinese champions and the Japanese title winners and cup holders, Lee scored six goals in two-and-a-half games, despite suffering from a cold.

He was at it again the following month, tormenting Saudi Arabia champions Al Shabab in the quarter-finals of the Asian Champions League as his team won the first leg 6-0.

He was quick to play up his achievements. “In my career, there hasn’t be any luck,” he said. “Pure sweat and effort made me the player I am now.”

But more controversy was just around the corner. After Ulsan were surprisingly knocked out in the semis, a frustrated Lee let rip a verbal volley at a referee in a domestic game – a serious offence in Confucian-influenced South Korea. He was sent off, banned for the rest of the season and ordered by the club to do three days’ community service.

His appearance at the disciplinary hearing was greeted by a posse of pressmen. “That’s another reason why he needs to leave,” says Pim Verbeek. “He’s too big and too good for the K-League. He’s done everything he needs to do here.”

For now, Lee intends to come back – and go out – with a bang at this month’s FIFA Club World Cup in Japan. Catch him if you can: the next time you see him could well be up against the Socceroos in a crucial Asian Cup clash. Groomed by footballing royalty, Adrian Leijer is the defensive kingpin in Melbourne Victory’s charge. And 2007 could be the year “the Prince” cements a place in the Socceroos

AGE 20

CLUB Melbourne

POSITION Defender

LOWDOWN Dubbo kid with a Dutch dad is another of Ernie Merrick’s VIS grads

You could say Melbourne Victory’s Adrian Leijer’s rise up the football ranks has been by royal appointment.

Supervised by coach Ernie “The Earl” Merrick, and with a little guidance from “Sir” Geoffrey Claeys, “Prince” Adrian Leijer has been a rock in a superb Melbourne Victory side this season. But hob-nobbing with Victorian football royalty is a far cry from his footballing roots – the tough as nails Dubbo junior football scene.

“My dad was probably the one who encouraged me to play football the most,” says Leijer, who grew up in country NSW, close to where Orange-based Nathan Burns began his own footballing education. “I played in the local competitions and made the representative sides. Dubbo would play against Orange… I’m two years older than Nathan, so I didn’t play against him but probably would’ve seen him around.”

As Australia went Olympics mad in 2000, the Leijers moved from Dubbo to the popular surf spot of Jan Juc in Victoria (about two hours drive from Melbourne), where the then 14-year-old flew through the development system He captained Victoria Country at the 2001 National Talent ID Championships at U15s and again in 2002 for the U16s.

Soon, Leijer came to the attention of respected youth coach Ernie Merrick, first at the Victorian Institute of Sport (VIS), where Merrick and his Victory assistant coach Aaron Healy ran the program, and later at Melbourne Victory, where Merrick signed Leijer in 2005.

“Adrian was truly a stand-out player,” says Victory coach Merrick. “He came to the VIS at 15 and his development has accelerated at every level. He got an opportunity with Melbourne Victory at the start of last season when Mark Byrnes was injured and has barely missed a game since.”

“The VIS helped me understand things outside of football,” notes Leijer, clearly still awed by his experience. “Such things as the right way to train and eat; to look after your body and prepare. It was a very important step for me.”

This step prepared him for a senior career that arrived a little sooner than expected in 2003. At just 17, Leijer made 20 appearances for Melbourne Knights in the old National Soccer League. It was an ideal league to learn in – and toughen up – with lessons being dished out by hard-boiled strikers such as Damian Mori, Stewart Petrie and Joe Spiteri on a regular basis. That same year, Leijer was selected in the Joeys squad for the World Championships in Finland.

But it’s been at A-League level that Leijer has flourished. Despite the disappointing seventh placing last season, Leijer was crowned Clubman of the Year and Players’ Player of the Year at the Victory aged just 19.

Much of Adrian’s top flight success is due to the help of former Victory defender “Sir” Geoffrey Claeys. The respected Belgian international and former Feyenoord and Anderlecht player has provided valuable guidance to the youngster over the last two seasons.

“I have learnt a lot from Geoff,” says Leijer. “He would stay back at training, even when he wasn’t playing in the first XI, and he’d be giving us tips and helping us with our positioning.”

It says much about Adrian, as well as team-mates Roddy Vargas and Daniel Piorkowski, that Claeys was not able to break back into the first team, prompting the veteran to return to Belgium.

Playing alongside Vargas and Piorkowski – who Leijer played with three years ago at the humble Knights Park – has helped gel the defensive unit, making Victory the best defence in the A-League (11 goals conceded in 16 games at time of writing).

The Dubbo lad has also proved he’s not one to be messed with in what is a physical A-League. The 20-year-old’s bodycheck on Robbie Middleby during that combustible derby with Sydney in round two is ample evidence of his willingness to put himself about. Other strikers too have felt the sting of this AFL fan’s physical approach.

Leijer looms as a key man for club and country in the next few years. Victory’s A-League dominance appears set to continue, while he has a chance to play in the 2008 Asian Champions League. In the coming year, there are spots up for grabs as Arnie’s Olyroos head into a particularly tricky and demanding chunk of Olympics qualifiers across Asia.

What’s more, with speculation that Guus Hiddink will be back for the 2010 World Cup campaign – with Graham Arnold in tow – Leijer is ideally placed to stake a claim for a senior spot over the next few years.

The 2007 Asian Cup could be an ideal jump off point for the youngster. He has already had a taster, having been selected as a World Cup train on player in May and again in August for an Asian Cup match.

“Guus keeps to himself,” Leijer recalls of the Dutch master. “He has a presence around the place that gets the players buzzing and gets their confidence up. Every training session you could see the massive respect the players had for him… with my background being Dutch, he asked me about that but he was focused on the World Cup players. It was a great experience and something I’ll never forget.”

Now, the question is, who will partner Lucas Neill in the next few years at the heart of the Socceroos’ defence?

With the retirement of Tony Popovic and Tony Vidmar, and with Michael Beauchamp falling behind in the pecking order, Leijer may be in the box seat for a place in the centre of the green and gold backline.

With so much happening internationally and in the booming A-League (“It’s like playing in Europe at Telstra Dome with the size of our crowds”), perhaps it’s no surprise then that Leijer isn’t too keen to rush off to Europe... at least not in the short-term.

“It’s something that every player dreams of and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want to also go overseas,” says Leijer, a Manchester United fan. “But with the Olyroos and the way Melbourne Victory is set up, there’s no reason why I can’t stay here for a few more years.”

Melbourne Victory will be hoping “Prince” Leijer’s reign is a long and fruitful one.

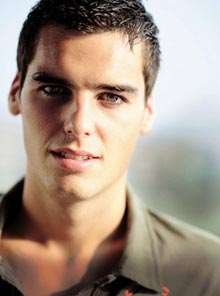

AGE 23

CLUB Marseille

POSITION Winger

LOWDOWN Fiery Frenchman who’s yet to settle at club level. Another move awaits.

Twelve months ago, not many football fans in Britain had heard of Franck Ribery. Hardly surprising, given that he was still playing in France’s Third Division in 2004. Back then nobody could have predicted he’d be one of France’s leading lights in an improbable run to the World Cup Final two years later. But now, aged 23, the boy who grew up on a rough council estate in the north of France dreaming of being the next Chris Waddle, has the world at his feet following a roller-coaster ride that has seen him first jump two divisions to France’s top flight, then scarper to Galatasaray for a six-month fling before returning to Marseille, setting Le Championnat alight with his trickery and joie de vivre, and forcing his way into the World Cup side alongside another of his boyhood heroes, Zinedine Zidane. As Ribery says: “It’s mad!”

And yet here we are predicting even greater things to come for the winger they call ‘Scarface’. Because the Ribery story, all Boy’s Own stuff with its unlikely twists and turns and rags-to-riches story arc, is set to continue on it’s upward climb. A host of big clubs are primed to pounce and Marseille are resigned to selling him to an overseas side to prevent him going to French champions Lyon.

Meanwhile Ribery, after a breakthrough 2005-06 season in France, where he won the Player of the Month award three times, was named Young Player of the Year and scored the Goal of the Season (a thumping 30-yard volley against Nantes), has shown that the better the level of competition, the better he plays. He got his first taste of the cream of world football in Germany last summer after his meteoric rise thrust him into Raymond Domenech’s France team and now Ribery wants more. Next season, he intends to be playing in the Champions League, and England should be the place he gets his chance.

“Franck is now a very big player in Europe and it’s true the biggest clubs want him,” says his representative, Bruno Heiderscheid. And, for once, we’re inclined to agree with an agent. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s go back to the start, to the grim northern port town of Boulogne-sur-Mer, where Franck Ribery was brought up and his problems began.

At the age of two, a horrific car crash saw little Franck go through a windscreen and pick up the scars down the side of his face that have marked him ever since.

“I was very young and I don’t remember what happened, but it was pretty serious,” explains Ribery, who has come to wear his disfiguration with a defiant form of pride after years of denigration.

“In fact, it’s not really the accident that has caused me the most problems as I was so young. It was more the way people looked at me. There were some who would take the mickey, and my family had to battle against that. I grew up with that. Now I’m earning a good living people often ask why I don’t have plastic surgery or something but I don’t feel the need. The scars are part of me, and people will just have to take me as I am.”

Like most of France’s working-class northerners, Ribery was brought up to speak the local patois, called ch’ti, a mixture of French and Flemish. And when he wasn’t at school or skiving, he’d spend his time at the foot of his dilapidated block of flats, kicking a ball around until dusk in the

notorious Chemin-Vert estate on the edge of Boulogne. It was there that he met his future wife, Wahiba, who persuaded him to convert to Islam. And it was playing for Boulogne’s youth team that he was spotted at the age of 13 and invited to attend the academy down the road at Lille.

It should have been the beginning of something good for Ribery, the ticket out of his dead-end town. Instead he ended up back in Boulogne three years later, kicked out of Lille for not trying in his school classes and getting into too many rucks.

“I got thrown out because I wasn’t very good at school, mainly,” says Ribery. He still remembers how he felt on hearing Lille’s decision: “It was frightening. I said to myself, ‘Maybe that’s it, maybe I’ll never be a footballer.’ The toughest thing of all was having to tell my dad that I wasn’t at Lille any more. My dad’s the one who counts the most for me as far as football is concerned, he’s always been there by my side. Luckily for me, I went back home and managed to play again straight away with the under-17s at Boulogne.”

Jean-Luc Vandamme, the man who whisked him off to Lille, refutes suggestions that Ribery is none too clever and prefers to explain the reasons he always believed the skinny youngster he first noticed 10 years ago could go on to make it to the top. “Franck has great anticipation,” Vandamme says. “He analyses three times faster than others. On the pitch, he has all the problems worked out while others are still pondering. People think he’s thick but that’s pure stupidity – he is anything but. He has a practical intelligence, like all the great players.”

As another early coach, Jose Pereira, says: “Even a street lamp would have been able to see that Franck was a very good player, but you always had to keep your eyes on him, like a pan of milk on the boil. He was a kid who grew up in the street.”

|

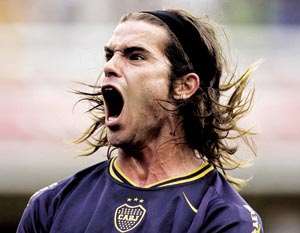

| Ribery introduces himself to the world after scoring against Spain last year. |

“When we signed Franck he was ever so shy, and was coming out of a really tough period in his life where there were a lot of problems to deal with,” says Fernandez. “But he already had the qualities that he’s showing today, the same dribbling skills and great acceleration. At Metz, he became the man with the most assists in the six months he was with us. Today of course he has more recognition because he’s at a bigger club with Marseille, but everything that’s happening to him is no surprise to me.”

Ribery proved to be an immediate hit at Metz, drawing comparisons with the club’s favourite son, Robert Pires. He was called into the France Under-21 side after some impressive displays, coping with the leap up two divisions with few qualms. But then Ribery showed his impetuous side, quitting Metz after half a season for the unlikely destination of Galatasaray. French fans were stunned. Six months on they were stunned again when Ribery, who had proved a big hit with Galatasaray, even scoring in their cup final victory over arch-rivals Fenerbahce, announced he was returning to France to join up again with Fernandez, now at Marseille. There followed a legal wrangle with the Turkish club, accused of not paying the Frenchman’s wages, and a bizarre public spat with a former agent, who reportedly turned up on Ribery’s doorstep in Boulogne armed with a baseball bat in a bid to resolve one or two little problems between the two men.

Still, Ribery was excited at the thought of playing in front of Marseille’s impassioned crowds of 60,000 at the Velodrome, where his idol Waddle had once strutted his stuff and where Jean-Pierre Papin, another of his heroes, had banged in so many spectacular goals. And he was overjoyed to be back with Fernandez.

“His presence was fundamental in my development, he was the one who came to get me when I was playing for Brest in the Third Division, literally picking me up in his car and driving me to the other side of France to convince me to join Metz,” relates Ribery. “He was the one who got me in the top flight and he contacted me as soon as he was appointed Marseille manager. Jean Fernandez represents the greatest encounter I’ve ever had in football. He’s my spiritual father and I think he considers me a little bit like a son. He’s the type of man you never forget, and he’s also one of the best coaches in France. And he’s even crazier about football than I am!”

Ribery quickly conquered the hearts and minds of France’s most demanding and passionate supporters with his whole-hearted performances, mazy runs, dribbling skills and sheer will to win. He was hogging the limelight with his displays and there was soon a campaign to catapult Ribery into the national set-up for the World Cup. Domenech resisted and resisted, only to end up naming him even though he’d never picked him before. The uncapped youngster was in, ahead of Ludovic Giuly, Johan Micoud, Nicolas Anelka and Pires.

Ribery, who’d watched the manager name the squad live on TV like us mere mortals, celebrated with a kickabout in his garden with his brother. When asked to explain his late inclusion, he summed it up perfectly: “I think people wanted to see me picked because I’m the kind of guy who never cheats. I give everything I have in my guts when I’m out there on the field and then of course there’s my background, my story. What’s happened to me shows that anything can happen in football, that you can come from a long way down the ladder to realise your dreams. I think people like that idea too. Nobody thought I could do it.”

Do it, though, he did, working his way from an impact substitute in the pre-World Cup friendlies to a starting place in the tournament. And, despite a few teething troubles, when the competition really got going Ribery showed he was ready. Having struggled through the group stage, France were up against a Spain team that was firing on all cylinders and, for once, favourites to beat the stuttering French. The Spanish went ahead, only for Ribery to strike his first goal for Les Bleus, running through the opposition’s backline before firing in the effort that lifted French chins and ultimately launched them on their run to the final. A star was born.

Like everybody else in the French camp, Thierry Henry was under the spell: "Franck always shows this will to go forward, the will to attack," Henry said. “There are very few players in the world today who can accelerate like he does, brutally. He plays with freedom and he can unlock a match at any moment. He plays with his heart.”

Post-World Cup Ribery was again involved in transfer shenanigans, claiming to have contacts with Arsenal, where he dreams of playing alongside his new buddy Henry, before announcing live on the nation’s most-watched evening news bulletin that he would be joining Lyon. Marseille, still regretting the departure of Didier Drogba to Chelsea, were having none of it and Ribery stayed.

The fans wanted to give him a hard time for his apparent lack of fidelity, but Ribery carried on as if nothing had happened, tormenting visiting defenders and running himself into the ground – so much so that the supporters soon found themselves cheering him on again. Ribery wins over fans because he is one of them in much of his attitude and behaviour. He has qualities they want to see: he’s a winner who will always try to take people on, and who isn’t afraid to turn on a show when possible.

“I play how I feel: I don’t have a set way of playing as I’m an instinctive type of player,” he says. “When I get the ball I don’t hang around to think about it, I get going, and I look to create as much danger as possible. My greatest strength is simply the fact that I love football so much. I’m an attacking midfielder, not a forward, but I can play up front, on the left or the right. I even ended up last season playing just behind the strikers. One thing for sure is I won’t change the way I play. I do what I know best. I’ve always been guided by pleasure, whether in Division Three or in the World Cup, and I don’t see why I should change.

“For me, football is full-time. I live and breathe it. And when I see my dad, who works in the building trade, get up at 7am every day and finish at six in the evening, I say to myself that footballers are lucky.

“Even if I lack experience I have youth and spirit on my side. Pressure has no effect on me, I never feel it, and as soon as I’m out there I want to be taking people on and setting up people, taking chances. Sometimes I improvise and try dribbles I never even imagined. I’m always looking to enjoy myself on the pitch, that’s what I love! You have to give people value for money, and it’s in my character to give my all, to try everything, to make my runs, to go past people, to dribble with the ball, the kind of stuff that gets people off their seats.”

Stewards around Europe, you have been warned. Next season, as the Frenchman flies down the wings, you’ll be telling a lot of people to sit down. AC Milan’s tyro opted for backheels over backhands when he chose to play football rather than tennis. New balls please.

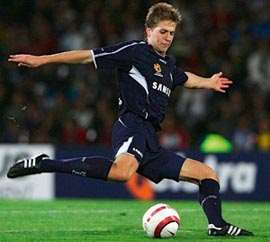

AGE 20

CLUB AC Milan

POSITION Midfielder

LOWDOWN He could have gone to Wimbledon... but only to play tennis

Yoann Gourcuff introduced himself to AC Milan’s fans in spectacular style earlier this season. Making his first start for the Italian giants since switching from Rennes a few months earlier, the 20-year-old Frenchman scored with a bullet header in his team’s 3-0 Champions League victory over AEK Athens. Although a relative unknown to most fans, Gourcuff’s transfer made ripples in France. Though the classy midfielder is expected to go on to great things, there was concern in his homeland that he might struggle to impose himself in Serie A. Gourcuff was having none of it.

“I really felt the time was right,” he explains earnestly. “I was ready for the challenge and where better to learn your trade, to take the next step forward, than at AC Milan?”

Gourcuff, whose father Christian is a former player and now manages French top-flight side Lorient, almost never became a footballer. Equally gifted at tennis, he only made up his mind a short while ago.

“I realised that it might be easier for me to make it in football,” he says.

It was the first of several difficult decisions he has faced in his fledgling career. After starting out at Lorient, where his father was in his first spell as manager, he had to decide in 2001 whether to follow papa to Rennes. Yoann initially wanted to join Nantes instead, causing his father to wonder what was going on and whether his son was as good as he believed he was.