HE became the world’s most expensive player when he moved from Manchester to Madrid for $140m. But can one man really be that good? FFT investigates his impact on club and country.

1. What impact has he had so far in Spain?

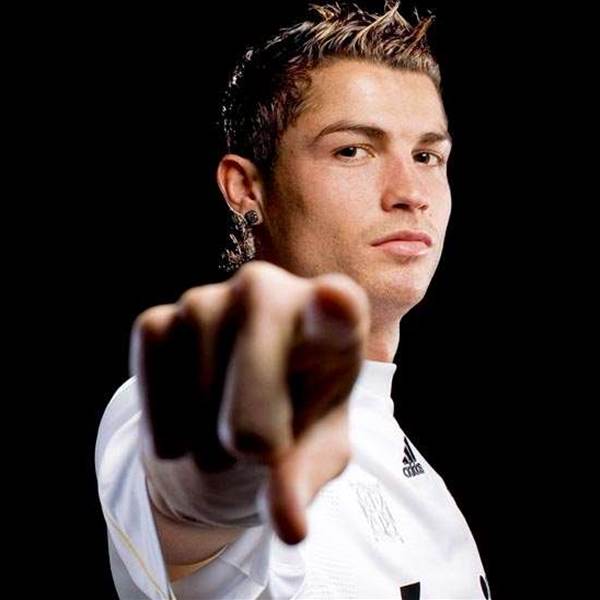

For the man who can do no wrong, even getting injured was the right move. In fact, it'd be tempting to say that it was the best thing he could have done - if he hadn't already done more than most fans expected. On the summer evening that Cristiano Ronaldo was unveiled at Real Madrid, the Santiago Bernabeu was packed. Some had camped for hours to get front-row seats; others were stuck outside. Eighty thousand people had turned out just to see him stride across a catwalk, perform a few kick-ups and shout: "¡Un! ¡Dos! ¡Tres! ¡Hala Madrid!"

Expectations couldn't've been higher, but Ronaldo met them. $140m? Worth every cent. He had eclipsed Kaka and would continue to do so. Here, at last, was the man who would break Barcelona. They say that patience is a virtue, but Real Madrid don't have the time. Nor, it seemed, did Ronaldo. Zidane took months to settle - but Ronaldo hit the ground running. Very, very fast.

On the first day of the season, he scored against Deportivo de La Coruna. The celebration was oddly endearing. Clenched fists, a huge grin, a kind of childish delight. It spoke of relief.

Pre-season had suggested that he felt under pressure. Actors aren't judged on dress rehearsals; Madrid's players are. One headline declared: "Ronaldo hasn't found his place", yet the season hadn't even started. Ronaldo, the ultimate performer, seemed desperate to win over his crowd. On the opening night - his first proper game - he took a step towards doing just that. He never looked back.

A month into the season and for the first time in over a year, Madrid were top. You didn't have to look far for the man to thank. Dashing in from a narrow left-sided role, Ronaldo frightened defenders, intimidated them. He seemed bigger than everyone else and about 50 times faster. When he ran, there was an air of expectation, a murmur, and palpable panic in those who faced him.

He combined well with Kaka - with whom he has become genuinely friendly - and his team-mates insisted there was no sign of the diva. "Ronaldo," said Marcelo, speaking for everyone,

"is a normal guy". He would say that of course, but the demeanour in training was good; the connection appeared genuine. When Karim Benzema complained that the sun was blinding him at one photo-shoot, it was Ronaldo who handed over his shades. A wonderful start short-circuited any potential clash with Raul.

Besides, Madrid's captain was the beneficiary - Raul got three in the opening two games. Manuel Pellegrini cooed over Ronaldo's endeavour. You only had to look at his rippling torso to see how serious he was. He was, they said, the first to arrive every morning and the last to leave. When he got home, he worked in his own gym. The media appeared to be trying to get him beatified, eulogising his every move.

The things that hadn't endeared him to people in England didn't count against him: the step-overs and flicks were welcomed, even when they took him nowhere, even when they were pointless. Emboldened, delighted by appreciative oohs, playing to the crowd, Ronaldo did them again. When he stopped dead, looking aggrieved and appealed for free ?kicks, he got them. And dives are in the eyes of the beholder; here, Ronaldo was "fouled". In La Liga, "provoking" free kicks and penalties is a skill.

Only in Catalunya was he criticised, but every Madrid player gets criticised in Catalunya. The one surprise was that mild-mannered Andres Iniesta had a go at him, too: when Ronaldo accused the Barcelona player of diving, Iniesta told him to "shut it". "I didn't think he was the right person to complain about that," Iniesta explained. Touché.

That night, Barcelona's fans revived their Luis Figo chant. "¡Ese portugés, hijoputa es!" "What a son of a bitch that Portuguese is!" They wanted a hate figure; and a preening Ronaldo fit the bill. But it didn't convince; sure, he seemed arrogant but Ronaldo was not Figo. It was more about fear than loathing. And that was hardly surprising: every time Ronaldo began a run, alarms rang. He scared them. He scared everyone.

"Ronaldo has the power to change the result," said Madrid's director general Jorge Valdano, "and that's the greatest power of all." Five league matches, five league victories and five league goals. Against Xerez, he dashed past three men and thumped a shot low into the net. Against Villarreal, he opened the scoring after two minutes with a similar goal - an early contender for the season's best, picking it up just inside his own half and burning past defenders before finishing with an unstoppable shot.

Madrid were banging them in. In the Champions League they thumped Zurich 5-2 with two free-kicks from Ronaldo. "Ronaldo," said Roberto Carlos, "turns free-kicks into penalties." No one seemed to notice that Zurich's keeper had punched one into his own net and simply misjudged the other. No one wanted to notice - they were enjoying Ronaldo too much. And against Olympique Marseille, he scored two more in a 3-0 win. Madrid topped the group with eight goals in two games. Ronaldo was the tournament's top scorer. He'd got nine goals in seven games; only once did he fail to score.

Madrid weren't playing well, but it didn't matter because Ronaldo was. As one report in El Pais put it, "Madrid win because they have the bomb." He was, said the headlines, "a goal-machine", "a beast". A new word came into fashion: ‘Ronaldodependencia'. "He's as decisive as he was at Manchester United," Valdano said. "When you have one of the best players it's logical that you virtually abuse him." A poll showed most fans thought Madrid depended on him. "Ronaldo is crucial to us," said Xabi Alonso; "Ronaldo is fundamental," admitted Kaka.

They were about to find out just how fundamental. "I don't think the team relied on me," Ronaldo later insisted but the evidence suggested otherwise. He had scored twice against Marseille but also picked up an injury. A set-back playing for Portugal, a new diagnosis, the discovery of a problem with his heel ... in total, he was out for 56 days, every one of them crossed off anxiously, like a prisoner waiting for parole. When one front-page headline declared "another month out!", you could almost hear them hacking at their wrists.

Everyone had been fascinated with Ronaldo - and in his absence, fascination became obsession. Nearly half of the covers of Marca, the country's best-selling daily, were dedicated to him in October - a month in which he didn't play. "Cristiano," admitted the paper, "casts a long shadow."

Madrid's first game without him ended in defeat against Sevilla. Seven wins in seven became two wins in seven. Worse, one of those was against Alcorcon from Second Division B - Spain's equivalent of the state league: a 4-0 Cup hammering declared the greatest humiliation in Madrid's history. Without Ronaldo, Madrid stumbled from poor match to poor match. When he returned two months later, he was still their top scorer in the league and in Europe.

Who knows, maybe Madrid would have lost against Milan, Alcorcon and Sevilla with Ronaldo too; maybe they would have failed to score in Gijon and blundered to a gutless, impotent 1-0 win over Alcorcon when chasing four goals in the second leg. But it seemed unlikely.

And no-one - absolutely no-one - saw it that way. "More than Cristiano being important to Madrid, Madrid are making Cristiano important," remarked Barcelona defender Gerard Pique.

"Every time they don't win, they attribute it to him not being there." Pique was quite right. But then so

were they. When Madrid lost to Sevilla, Marca's cover declared: "Cristiano is mucho Cristiano." As he entered the final stages of his recovery and prepared to play 30 minutes against Zurich in the Champions League, still the tournament's top scorer two months later, the Madrid-based sports daily AS let out a relieved cheer: "The man returns: Cristiano plays!" "He's here!" said Marca, "Madrid get their leader back." "He's coming! He's coming!" ran another headline.

About time, too. The Madrid-supporting columnist Tomas Roncero was reaching the end of his tether: "Cristiano," he pleaded, "do something!"

So Cristiano did. A colossal roar greeted him as he warmed up with Madrid labouring against a poor side. "Cristiano rides to the rescue," cheered AS's front page. "He played 24 minutes, gave 10 passes, took four shots, did two dribbles, and almost scored." "The only good thing of the night: Cristiano," agreed Marca's cover. "He had more shots in 21 minutes than Raul and Higuain in the whole match... His very presence changes the face of Madrid."

Suddenly, all was well with the world, perfectly timed for the clasico. Now, Madrid could face their rivals with hope. Their saviour, the world's "undisputed" best player, had arrived. Asked if he'd like to score, he replied: "Yes, 10 or 20, or a thousand goals." It was meant as a way of dismissing a dumb question but it

only added to his legend - in Madrid he was a determined, ambitious warrior; in Barcelona, an arrogant sod. It was all about Ronaldo; his moment had arrived. In the 19th minute, it really did. Kaka cut in and slotted the ball into Ronaldo's path. Fifty six days later, this was it.

The moment they'd all been waiting for. Impatiently. Obsessively. Madrid really did depend on Ronaldo, and now he was here. He was going to score, they were going to beat Barcelona. He took two steps forward, struck the ball with the inside of his right foot... and it flew straight at Victor Valdes. The moment was lost and so, ultimately, was the match. For the first time, Ronaldo had been on the losing side with Real Madrid. Well, no-one's perfect. Not even the perfect.

2 How much have Man United missed him?

Anyone watching Liverpool humiliate Manchester United at Old Trafford last March would have been forgiven for assuming that the visiting team would be crowned champions of England a couple of months later. Driven on by the muscular predator Fernando Torres, the Merseysiders hammered their north west rivals, scoring four times and leaving visible psychological scars all over the home defence. What's more, it was the second time Liverpool had beaten United that term.

Yet, when the Premier League trophy was handed over, it was into the ever-grateful palms of Sir Alex Ferguson. United might have been smashed that day by their nearest challengers, but over the season they still managed to garner four more points. This was largely because Ferguson has long since recognised this enduring truth of league life: the number of points for a routine win over a side destined for relegation is exactly the same as those available in a spectacular victory in the home of your championship rivals. Put simply, he won it because he did not forget to win at Wigan.

Rafa Benitez seemed unaware of this fact: with his leading practitioners often rested for challenges ahead, his team dropped 12 points at Anfield in 2008-09. United, meanwhile, accrued 58 points out of a possible 60 against the bottom 10 clubs; the only blemish on a seamless record a draw with Newcastle.

It was an astonishing performance, one achieved in no small measure thanks to the goals provided by Ferguson's number seven. Thirty-nine of those points were gained in matches in which Cristiano Ronaldo scored. Of all the qualities displayed by the world's best player, his ability to destroy lesser rivals was perhaps the most valuable to his former employer.

The living refutation of ancient prejudice about ball-playing foreign players, Ronaldo loved nothing better than turning it on on a wet Saturday at Bolton. Not that this is to say he was merely a flat-track bully: his goals against Chelsea and Arsenal in the latter stages of the Champions League proved he enjoyed rubbing the snootiest noses in the mire just as much.

But while his pace, power and searing skill were all invaluable, it was the sense of invincibility he brought to his side, the feeling that whatever a rival might do, he would do better, that was so compelling. Opponents would take one look at the team sheet, see his name thereon and mentally assume the position.

Sadly for Ferguson, he was aware he had only the most fleeting access to such an asset. Whatever he might have said publicly, he knew for certain after the flirtation between the player and Real ??Madrid in the summer of 2008, he would soon be gone. But having time to think how he might resolve it didn't make the problem of how to replace him any less intractable. How he coped with life after Ronaldo would be the defining issue of the last phase of his management.

In the first instance, Ferguson bought not one but two wide men. Antonio Valencia and Gabriel Obertan were never suggested as plausible substitutes for Ronaldo, their acquisition more to do with the balance of the side. Valencia, the stony-faced Ecuadorian, is broad-shouldered, physical and intelligent. Obertan is lightening quick; ridiculously so. Even between the two of them, however, they do not boast sufficient qualities to match up to one Ronaldo. Neither provides the sense of invulnerability he brought to a red

shirt. And six strikes between them at the time of writing suggests neither will they replace the goals.

But Ronaldo's departure has exposed wider fissures in Ferguson's United than merely those on the right side of his attack. The manager has issues across the team. Edwin van der Sar, Paul Scholes, Gary Neville and Ryan Giggs are all out of contract at the end of this season - and despite their advancing ages, perhaps only Neville has serious rival for a first-team berth. Several of those bought to replace the ageing quartet have failed to deliver: after undermining the manager publicly, the flaky Nani is on his way out, Anderson is inconsistent, Berbatov a chimera, Foster has looked about as resilient as wet cardboard and as for Owen Hargreaves, rumours of his continued existence have become increasingly difficult to verify. Worse, Nemanja Vidic, the rock around which the manager intended to construct his defence for the next five years, has shown signs of restlessness even as his defensive partner Rio Ferdinand has begun physically to fall apart.

Last season, all of these were issues, but Ronaldo's goals helped disguise them, paper over any cracks they might produce. Two trophies were brought to Old Trafford by a team in transition.

It seemed a miraculous piece of management by Ferguson, but he knew who to thank.

Not that United are terminal: any side that can boast within its ranks players like Darren Fletcher, Patrice Evra and the chronology-defying Giggs can hardly be characterised as lacking in resources. Plus there's Wayne Rooney, who has taken responsibility following Ronaldo's departure to seize the initiative in the team. Rooney's performances this season are the reason Ferguson sleeps at night, his strength and determination steering them to second place in the league, having scored more goals at this stage of the season than they had last year.

Yet something left with Ronaldo: that air of certainty he projected. Without Ronaldo, United have already this term dropped twice as many points against the lesser teams as they did throughout the whole of last year, this in addition to losing at Chelsea and Liverpool. The easy answer for Ferguson, critics suggest, would be to spend big in January. Why, they wonder, not use some of the $140 million accrued from Ronaldo's sale to bring someone like Frank Ribery or David Villa on board? But good players as they are, it is a big ask to expect them immediately to fit the United template quite as perfectly as Ronaldo did. The Portuguese was the embodiment of Ferguson's style, the finest exponent of counter-attack ever to pull on a red shirt. Ferguson built a team, a system around the player's strengths, happy to sacrifice those like Van Nistelrooy, who didn't fit its parameters. For five years he reaped the rewards in the shape of endless silverware. Now his creation has gone, there's a hole the size of Ronaldo's ego in his team. It remains to be seen if there'll be an even bigger gap in his trophy cabinet.

3. Can Ronaldo Win Portugal the World Cup?

Outside Britain, the captaincy is not generally seen as a matter of endless debate. Wearing a strip of cloth across your bicep does not make you a captain, in the same way that not wearing an armband does not make you anything less of a leader. Yet when Cristiano Ronaldo was chosen to captain his country it raised eyebrows - especially when Carlos Queiroz named him as the permanent skipper after Luiz Felipe Scolari gave him the armband for Euro 2008.

Cynics said it was a way of making the Real Madrid star "more responsible" and of stiffening the link between Queiroz, who has often come under fire, and Ronaldo, who remains off-limits in terms of criticism.

As one Portuguese pundit put it: "Queiroz is an easy target. This is a way for him to hide behind Ronaldo."

And so, at the tender age of 24, Ronaldo finds himself the quintessential "captain who leads by example", largely because his vocal and charismatic skills within the dressing room are not on a par with his playing.

The problem is, when you're so much better than everybody else, it's hard to "follow your example".

His predecessor, Luis Figo, set the bar high. Figo was a great player and a charismatic leader the nation could rally behind. Ronaldo doesn't fit that mould, which is why, if you watch Portugal play, you'll notice much of the leadership comes from defender Bruno Alves and midfielder Deco (whose Brazilian accent and roots pretty much disqualify him as skipper material, but who would have been a natural choice).

Then there's the fact that Ronaldo hasn't played too well in a Portugal shirt. He failed to score in seven appearances during their qualifying campaign. In fact, he's scored just one goal for his country since Euro 2008: a penalty in a friendly against Finland back in February. While he contributes much more than goals, it's what Portugal needs most right now is a goalscorer. They haven't had one since Pauleta and some might argue they haven't had a great one since Fernando Gomes retired some 20 years ago. Indeed, that's why Brazilian-born Liedson was naturalised in a hurry in August.

Given the dearth of options, Ronaldo has little choice but to play up front, alongside Liedson. The one variant is represented by Hugo Almeida, a strapping old-school centre-forward who does a fine job for Werder Bremen but often comes up short for his country, as evidenced by the fact that he has scored in just four of his last 17 outings with Portugal (of those four, two came against Liechtenstein, with one each against Malta and Albania).

Pepe, ordinarily a central defender with Real, anchors the midfield alongside the hard-running Raul Meireles; plenty of graft to support the tricky, mercurial wingers, Simao Sabrosa and Nani. The real strength of this team, Ronaldo apart, could be the defence. The pairing of Alves and Carvalho, shielded by Pepe and with the Chelsea duo of Paulo Ferreira and Jose Bosingwa on the wings has proven to be tough to break, as evidenced by the seven clean sheets kept in 10 qualifiers.

This all points to a more workmanlike side built on a solid foundation, but perhaps overly reliant on Ronaldo. Keep it tight, don't concede goals and wait for your superstar to do something? It's worked for lesser teams in World Cups past. Provided Ronaldo gets hot and stays hot, Portugal will be in the running.

This article appeared in the March 2010 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. To buy back copies of this issue call 03-8317-8121 with a credit card to hand.

Related Articles

Postecoglou looking to A-League to 'develop young talent'

.jpeg&h=172&w=306&c=1&s=1)

Big change set to give Socceroos star new lease on life in the EPL