After Johnston’s first game, Boro manager Jack Charlton called him “the worst footballer I’ve ever seen” and ordered him home.

After Johnston’s first game, Boro manager Jack Charlton called him “the worst footballer I’ve ever seen” and ordered him home.

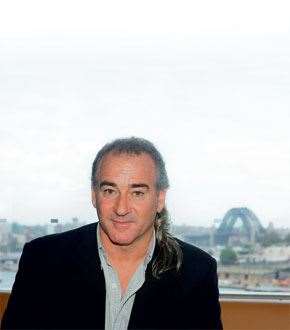

Craig Johnston

Craig JohnstonImage: Professional Footballers Australia

Australians are today spread throughout the world’s biggest football leagues like spores of wattle. When, in 1975,

15-year-old Craig Johnston headed to Middlesbrough for a self-funded trial (after his parents re-mortgaged their house), it was unheard of. After Johnston’s first game, Boro manager Jack Charlton called him “the worst footballer I’ve ever seen” and ordered him home.

But Johnston hid in the Middlesbrough car park where he practised for hours every day, cleaning the players’ boots and hiding from the gaffer. When Charlton left, Johnston cracked the first team. The rest is history. Much later he was honoured for his remarkable career with Middlesbrough and Liverpool in which he overcame adversity, injury and rejection to forge a 271-game career in the English First Division between 1977 and 1988 before retiring at the remarkably young age of 27. He won nine major titles with the Reds, including five First Division championships, two Football League Cups, the FA Cup, in which he kicked a goal in the winning final, and the European Cup.

“Through his single-minded determination and ability to succeed at the game’s highest level, Craig Johnston was the catalyst that changed the thinking of Australia’s best young players,” says Professional Footballers Australia chief executive Brendan Schwab. “It’s arguable that no single individual has had as much influence on football in Australia as Craig Johnston.”

You may recall Johnston’s record transfer fee to Liverpool, the controversy which surrounded his not playing for Australia or England, the invention of the Predator football boot, a hotel mini-bar accounting system called “The Butler” (which he invented because Liverpool team-mates had been raiding his mini-bar) and a football skills program called “Supa Skills” into which he poured his fortune and which bankrupted him into homelessness and rock-bottom depression. Well, today he’s back on his feet, a resident of a gated community in Florida and a neighbour of Tiger Woods’. As the Socceroos show their style on soccer’s biggest stage, Inside Sport sat down with a true pioneer to revisit one of the most extraordinary lives in Australian sport.

You once said playing soccer for Australia is like surfing for England. Now the Australian Professional Footballers’ Association has given you a gong, the Alex Tobin Medal. Sounds like all has been forgiven …

I think so, yeah. We’ve all been young and it was a stupid thing to say, not least because there have been many brilliant English surfers (laughs). But I couldn’t play for Australia – it was impossible to travel back. It’s not like now – we weren’t pampered like today’s players are. But the bottom line was, whether I pulled on a Middlesbrough or Liverpool shirt, I was representing my country. Every time I went out for a drink at night I knew I was Australian and did the right thing. There’s no issue that I haven’t represented Australia. I’m a very proud Aussie overseas.

It must feel good to be a pioneer, to have inspired the guys who have played in Europe?

Yeah, it does. I read that 567 Australian kids have followed me and been contracted in Europe, and that’s not to mention those who haven’t. Their dream has been to go over and at least try.I grew up supporting Liverpool in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s watching Kenny Dalglish, Graeme Souness and later yourself, John Barnes, Ian Rush … And that support came from watching English soccer a week late on Friday nights, with that theme music. You’d have had a similar experience?

Totally. That was our Tuesday night. We’d watch Frank Garnett, Til Death Do Us Part, then “bup-bump-bump-bump-baarr-da-ba-bump”, the Match Of The Day theme tune. And I’d watch it, spellbound. Then next day in the quadrangle at Booragul High School there were about 12 of us, soccer tragics. And we used to dissect every player, every move, everything. And after three or four years of this, we were 12-13 years old, someone said, “Wouldn’t it be great to go over there and do it.” And somehow that stuck in my mind. And I was like, “Yeah.” But people said, “Don’t be stupid, how would you afford to get there for a start, and anyway, we’re not good enough.” And I certainly wasn’t. These guys were all older than me and they were better than me, so I secretly hatched a plan. I was too embarrassed to tell the older kids I was going.

You wrote some letters to a bunch of England clubs from an absolute football backwater. Did you really expect to get a reply? Was it naivety? Or did you fair dinkum think you were good enough to play in England?

Yes and no. I wrote to them, but I didn’t know if I’d get a reply. We wrote to Tommy Docherty, Dave Sexton … big managers. Chelsea, Man U. Jack Charlton was at Middlesbrough and he’d toured Australia the year before, so we knew he knew Australia was on the map. His was the only letter we got back, saying that if you pay your fare and some money for board and lodging, we’ll let you have a trial.

Liverpool highs: “I don’t think the world has seen team spirit like it.”

Liverpool highs: “I don’t think the world has seen team spirit like it.”Image: Getty Images

Your parents were okay with their 15-year-old son going to England?

My mum was a teacher – she said the most important thing was my grades, but I said I wanted to go to England. Dad had gone there aged 20 and didn’t make it because he went too late. He said if you’re going to go you have to go young. But the decision was up to Mum. She said, “We’ll pay your fare [though they couldn’t afford it] if you come first in science, maths and English. So I studied like a lunatic for a year and a half and came first. My parents had to sell the house to finance the trip. So it was a pretty big deal.

Initially things didn’t go well, though …

In my first trial we were getting beat 3-0 at half-time. Jack Charlton had a go at everybody, then he pointed to me and asked, “Where are you from?” I said, “Australia.” He said, “Well, you are the worst footballer I have ever seen in my life and you’ll never be one while your backside points to the ground. Now hop it back to Australia.” Though, he didn’t say “hop it”. He totally destroyed me. I burst into tears and didn’t even finish the game. Soaking wet, I went back to the digs, tried to phone Mum and Dad for an hour, which was almost impossible in 1975. But I finally got through. Mum was all excited, asking, “How was the big game? Did Jack Charlton like you?” This, after having sold their house. I said, “Mum, Jack said I’m one of the finest players he’s ever seen and he wants me to stay.” And I hung up the phone before I burst into tears again. And then it was, “Now what the hell do I do?”

What the hell did you do?

Some of the senior players heard about the roasting I got and thought it wasn’t fair. So they said, “If you clean our cars and boots, we’ll give you some money so you can stay somewhere so you’re not out on the street.” So they went against Jack Charlton’s word. They said, “You can train in the car park, next to the mortuary.” Every time Jack would come into work, they’d warn me, “Jack’s coming, Jack’s coming,” and I’d hide behind the cars. Same thing when he left. They all thought it was hilarious.

But it was there where you truly honed your game …

I was in that car park for about a year, maybe 14 months, before Jack moved on. Every day I’d spend hours a day, left foot, right foot, dribbling, passing, shooting, volleying, nine hours a day. I’d train until I was in tears almost, then I’d do all the jobs, and the other apprentices would give me jobs: clean the toilets, clean the sauna, clean the baths after the pros had gone. But it gave me access to the boot room so I could borrow boots. They didn’t know because they were in the pub. I had top-quality Puma, Adidas boots. It was my pay-off.

Lonely times?

It was only two-and-a-half years, but it was nine hours a day, in jail in a car park. I had one job in life, which was to be a better soccer player that night than when I woke up that morning. It was probably the worst period of my life, but looking back it was probably the purest and the best period. I’m almost 50 now, and having been in business, bankrupted, achieved stuff and having everything taken away, you look back and see what was important. And those moments were so desperate and horrible when you had nothing, but they were also the finest, because I had a clear mission.

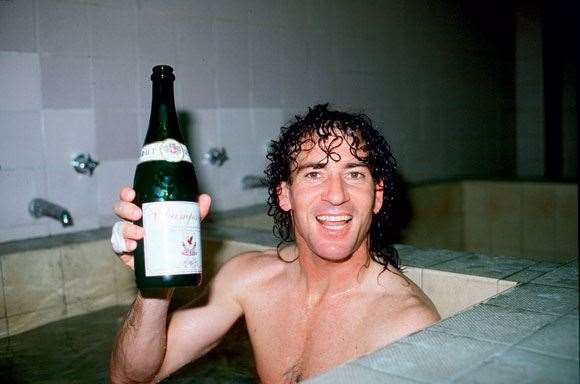

Bubbly sure beat cleaning boots and hiding in a car park for months on end.

Bubbly sure beat cleaning boots and hiding in a car park for months on end.Image: Getty Images

So Charlton moved on and you played 70 games for Middlesbrough and established yourself there.

After Jack left I started to play really well. We got a new manager, John Neill, who became a father figure, and encouraged me. When I did make the first team the quote from Jack Charlton was, “I always knew the Kangaroo was going to make it.” I was thinking, “You son of a gun … ”

Then Liverpool picked you up for three-quarters-of-a-million pounds, making you the most expensive player in Britain. Were you shy meeting Kenny Dalglish, such a legend of Liverpool football? And then to play with him?

Mate, I’m still shy meeting Kenny. He came and stayed with us for ten days last year (in Isleworth, Florida) to play golf – he’s a mad golfer, he and Alan Hansen. I’m still shy. He’s still King Kenny. I still pinch myself. The thing is that I also helped Kenny to look good because I was the opposite to him. He knew that I’d run off him and it would confuse defenders. The lovely thing is that he knows that without people running off him, he wouldn’t look so good. It’s good that way, football. The true stars recognise that’s what’s happening.

Those Liverpool sides of the ‘80s seemed particularly close …

When you were a Liverpool player, when you got the ball, three people were running off you, so you had three options, which gave you more time and made you look good. Because the players liked each other. You knew it was going to be hard work, but there was no issue because you liked the bloke. So the defenders are confused and your mate has more options. Watch the television. If there’s a team where a couple of players don’t like each other because of ego issues, they don’t run for each other. It was a Liverpool secret: the classic champion team, not a team of champions. Back then we didn’t know about real scientific athleticism, so we had a saying: “Win or lose, hit the booze.” So after games we’d have crates of beer being loaded onto buses by the coaches. They called it “liquid team spirit”. I don’t think the world has seen team spirit and camaraderie like it. And every one of those guys was an absolute gentleman and a bright guy. History has proven that every one of those guys has gone on and done something substantial, be it broadcasting or whatever. There was never any scandal, disrespect for women, drug abuse. And it’s testament to the professionalism back then. Each player was a good bloke who you’d run your heart out for. And if there were egos, they soon got lost in the quest for the greater cause

You were heavily involved in the FA Cup win in ‘86, scoring the goal to put Liverpool ahead, after almost claiming Ian Rush’s first one. Is that the standalone career highlight?

Well, there was a European Cup, the FA Cup. But really, I’m still a fan of the game. Pulling on a Liverpool jersey, a Middlesbrough jersey, they were highlights. Winning the FA Cup and the double … only three teams that century had ever done it … and it was particularly entrenched that year because Everton could’ve won the double also. So the two best teams in Europe were in the same city, one red, one blue. It was extremely intense. Most of the season Everton were winning the League, so the last ten games were like being in a war-zone. We had to win every one to win the double and we did. When I scored the goal it was like time slowed down. Players talk about being in a zone, but when that ball came across it was like someone slowed the video down. I thought, “Hang on, this is Wembley Stadium, it can’t be this easy. There’s the ball coming over, the goalkeeper’s already dived, there’s the clear, white posts, the cross bar.” It was a lovely, sunny day and there were 45,000 red scarves in the background. And then I put it in and the world erupted. Players were all over me and I remember saying, “I’ve done it! I’ve done it!” But I didn’t mean that I’ve scored a goal. I meant that I’ve come from the quadrangle of Booragul High School and I was now one of those blokes I used to watch on television. Then I was hoping beyond hope that Everton didn’t score and thank goodness Rushy scored another one. It was a good night.

Johnstone, leading the charge of Australian players into Europe. Image: Getty Images

Johnstone, leading the charge of Australian players into Europe. Image: Getty ImagesFinish this line from a popular UK pop song: “Well I came to England looking for fame / So come on Kenny man, give us a game / ‘Cause I’m sat on the bench paying my dues and my fees / I’m very big Down Under … ”

“But my wife disagrees.” [Laughs] They used to have these Cup final songs, and they were dreadful. So I’m sitting with my room-mate Bruce [Grobbelaar] and saying the music is crap when someone approached us and asked if we’d do this Liverpool song, like a marching band. Rap music was just starting out and I loved Run DMC and guys like them, and I said, “I’m going to write a rap.” Rap is about inner city gangs singing about their posse and we had a posse at Liverpool and they all had a foreign language or accent, along with the two Scousers, McMahon and Aldridge. It was a silly idea but it went to number three on the charts. Not bad given Madonna was number one!

So outside of your football you’ve had the songs, the Predator boot, Supa Skills football clinics, a “butler” application for hotel mini-bars that counted drinks … Are you always dreaming big?

Yeah – and doing big. I’ve always had interesting ideas. I’ve got a creative, fertile mind. And I’m a bit of a romanticist, I guess. I think of funny things, especially after a beer. I have great ideas and dreams – fantasies if you like – and they come back at me. It’s the “how” that fascinates me as much as the dream. I appear to shoot from the hip, but process and procedure is my thing. The thing I think I’ll be remembered for used to be called Supa Skills – it’s now called the Johnston Academy. It’s a blueprint for whoever wants to listen. At the moment FFA is not listening because they’ve never listened to me.

What is it?

It’s how Aussie kids get better on a daily basis at playing soccer. Everyone goes on about the Brazilian system, the Dutch system, Spanish, English. But there’s an Australian system that everyone’s missed. What I’m proposing is my ultimate dream in life: to bring the World Cup to Australia and for us to win it by playing better, cleverer football than the opposition, be they Brazilian, Dutch, whoever. Doing it the Australian way, because we have our own culture, identity, process and procedure, and our own sense of pride and getting things done. Why are we copying other people? There are more world champions per capita in this country than anywhere. Why aren’t the Dutch employing us to tell them how to get things done? What I’ve actually created takes the best of the Dutch, Brazilian systems and Aussie cricket, league, AFL – all sports I consulted ad nauseum. It takes the best of school teaching, best cultural influences. It’s not so much a coaching method as a scientific way of having fun on a daily basis and proving at night, when you get a scorecard, that you are better than you were this morning because you worked at your weaknesses. It’s very clever.

Liverpool highs: “I don’t think the world has seen team spirit like it.”

Liverpool highs: “I don’t think the world has seen team spirit like it.”Image: Getty Images

You’ve been spruiking your clinics for 20 years to various football bodies. Everyone always says no. It’s cost you millions of pounds, bankrupted you. Why?

Simple answer: it was ahead of its time. It was a visionary project. And I always was ahead of my time.

Why spend your own money on it, though? You didn’t think to get financial backers?

Money’s not the issue. Timing and common sense was the issue.

So why doesn’t the FFA pick it up and run with it?

In any sporting organisation you’ve got conflicts with technical departments and commercial partners. One of the reasons it hasn’t worked in the past is because commercial partners have said that what I do makes their programs look silly, therefore they can’t let it through. Governing bodies listen to sponsors because they pay the bills. So you’re locked into the politics of sport.

Why not get on board with the sponsors? Make it the Coca-Cola Craig Johnston Academy?

Ah mate, I can’t get into it.

You were bankrupt and reportedly homeless, yet you were once a millionaire player, feted by millions, living the dream. To be then living in a mate’s spare room – how low did you get?

Without dramatising it, as low as you can go. You don’t have a house, you don’t have a car. All the things you’ve worked for all your life … I invested my money in a grassroots program and people who said they’d back me didn’t for political reasons. I don’t need to say how low, but it’s as low as a bloke can go.

What dragged you out?

Ultimately it’s your friends and family and the things that are really important. I’d never failed before, basically. So recognising that it was all over was very tough. I walked away from the game and what I was doing and the thing I focused on, forgive the pun, was photography. I wandered the streets for a year. I forgot about the person I was because none of that was important any more. All the football business … now I was just a bloke. Photography had always been a love and a passion, and something that I’ve always done since I was 14. My first three or four wage cheques I earned as an apprentice with Middlesbrough I spent on a camera. Years later, at my lowest point, all of a sudden, all this pressure and the desire to achieve … it was gone. Everything I’d ever earned and built. I had nothing but this little camera that somehow the bailiff didn’t get.

A goal in the ‘86 FA Cup final at Wembley. Not bad for a boy from Oz.

A goal in the ‘86 FA Cup final at Wembley. Not bad for a boy from Oz.Image: Getty Images

Where did you watch the Socceroos’ famous win against Uruguay?

For the first leg I was sitting in an obscure bar somewhere in America. It was in North Carolina, a town called Durham. I had to hunt down a bar and bribe the bartender to switch the channel. We moved it to a Spanish network so I had the Uruguayan commentators. But I saw enough there to know this was a historic moment and I booked a flight the next day for the return leg and just made it to the stadium.

How about their loss to Italy?

I was in Kaiserslautern sitting behind Frank Lowy, John O’Neill and Sepp Blatter. Franz Beckenbauer was nearby in the VIP box. Mr Blatter invited me.

Dud result …

We were cheated, no doubt about it.

You like to invent things. What would you invent to stop that diving shit?

Decent refereeing! The funny thing is, I knew it was going to happen. Ah well – it was such a brilliant effort, but it was fate that we shouldn’t do it. It was cruel fate.

You live in Florida, a fair way away from the A-League. You catch much of it?

Every time I get home, two or three times year. I’m always surprised how much the standard is improving. These guys set out to make an A-League and put Australia in a World Cup, and they’ve done incredibly well.

What’s next for Craig Johnston?

I’m in this interesting stage of my life after having a lot of ups and downs. I recently received this award from the players’ union saying, “We want to give you something recognising that we think you were given a bit of a rough ride by the administration and media.” And these are words from someone like Craig Foster – who I respect – saying that all they knew was that I was a good player who didn’t want to play for Australia, but now they understand my story. There’s Colosimo, Bosnich, Slater saying, “Thank you for being one of us, a player, an Australian and standing your ground, we understand that it was the administration you had a problem with because they let you down, behind you there’s 567 kids with a contract who’ve followed you.” It was really emotional and there were tears galore. I didn’t expect that, to feel so humbled and welcomed.

– Matt Cleary

Related Articles

Champion A-League coach set to join Premier League giants

Emerging Socceroos star set to sign for MLS club