Ian Chappell’s forthright but enabling leadership transformed a dispirited Aussie Test outfit into the world’s most influential team.

Ian Chappell’s forthright but enabling leadership transformed a dispirited Aussie Test outfit into the world’s most influential team.

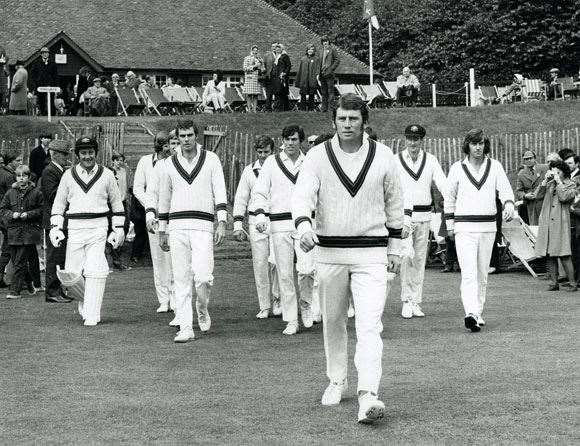

Chappell was a fine leader of men both on and off the field.

Chappell was a fine leader of men both on and off the field.Images: Getty Images

Ian Michael Chappell came along at a time when the earliest drafts of cricket’s obituary had been completed. By 1970-71, the world was on the cusp of massive change in all areas of life, and Test cricket – the only form being played internationally – was struggling to breathe under a muggy mantle of obstructive tradition.

When the grim Bill Lawry was unseated as captain in an ugly overthrow, Australia hadn’t registered a win in its previous ten Tests. Only a brilliant heretic was likely to prise it from the grip of despondency. Ian Chappell was a complex man with an uncomplicated vision; a courageous visionary, impervious to intimidation by men in suits or flannels.

In order to achieve his vision for his team, and cricket in general, such a man was bound to ruffle establishment feathers, and to command a team of cavaliers who did the same. It’s easy, in retrospect, to claim a team containing Lillee, Marsh, Thomson, Greg Chappell, Walker and Walters could virtually captain itself, but sometimes great leaders make certain selections seem logical where once they would never have been considered at all. And sometimes great leaders make great players. Chappell’s forthright but enabling leadership transformed a dispirited rabble into the world’s most powerful and influential team.

Then, after he retired from Test cricket after the 1975-76 series, he began phase two: the complete overhaul of world cricket. Having spent two years advising Kerry Packer in the lead-up to the greatest sporting coup detat ever witnessed, he resumed the captaincy for the World Series Cricket (WSC) Super Tests.

Like Richie Benaud before him, Chappell’s unfailing logic was leavened by the magic of intuition. His deployment of part-time bowlers like Ken Eastwood, Walters, brother Greg and himself proved successful time and again, because he was able to assess conditions and opponents expertly. Despite his strong brand of leadership, he was no tyrant, and was the first Aussie captain to play under the captaincy of his own deputy during tour matches.

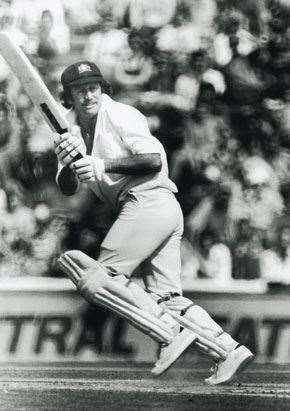

Chappell was able to assess conditions and opponents expertly. Images: Getty Images

Chappell was able to assess conditions and opponents expertly. Images: Getty ImagesBy the time the Aussies arrived in England in 1972, Chappell’s team had qualities English fans found hard to resist. They were one down for the Lord’s Test when Chappell pulled swing bowler Bob Massie aside and asked if he’d consider experimenting around-the-wicket to achieve a variety Chappell felt his attack lacked. Massie’s 16 wickets were the beginning of a renaissance. The Poms were rattled, and though they won another Test, the Aussies drew a series they were meant to lose. Furthermore, by the time the last Test, a slugfest won off Marsh’s bat, was won by the Aussies, the crowds were coming back to watch. The English were unused to five-Test series yielding four results.

Chappell always avowed that cricket had a simple aim: to bowl a side out twice. Every aspect of his game – fast-paced batting, intimidating field placements, unrelenting bowling, unprecedented fitness levels – was attuned to the achievement of that end.The interim period, before the Lillee-Thomson partnership, was marked by Houdini performances with a largely injury-plagued team. Chappell’s captaincy was often the difference. Severely criticised during the 1972-73 Pakistan series for declaring at 5/441 on the second morning of the Melbourne Test, Chappell won the match. The Sydney Test was won despite Pakistan needing only 159 for victory. In the West Indies, the Aussies emerged victors in one Test after the home side needed 66 to win with five wickets left. The Aussies won the series. Chappell made miracle wins seem commonplace, and by the time England came in 1974-75 – his last series as captain – his side was unconquerable.

Chappell lasted a then-record 30 Tests as captain, with only five losses, before the pressures of dealing with an unyielding establishment wore him down. He’d been the first captain to confer regularly with the Board on matters of pay and conditions. For that, he found himself constantly defending himself against accusations of being “inappropriate” and “unprofessional” for trivial peccadilloes like wearing a white floppy hat on the field.But having the last laugh was Ian Chappell’s specialty, and in 1977, with the advent of WSC, he flipped his last bird at the establishment and went about his usual business of transforming the game he loved.

– Robert Drane

Related Articles

Socceroo-in-waiting seals Championship deal

Fringe Socceroo swerves A-League to remain in Europe after Fulham exit