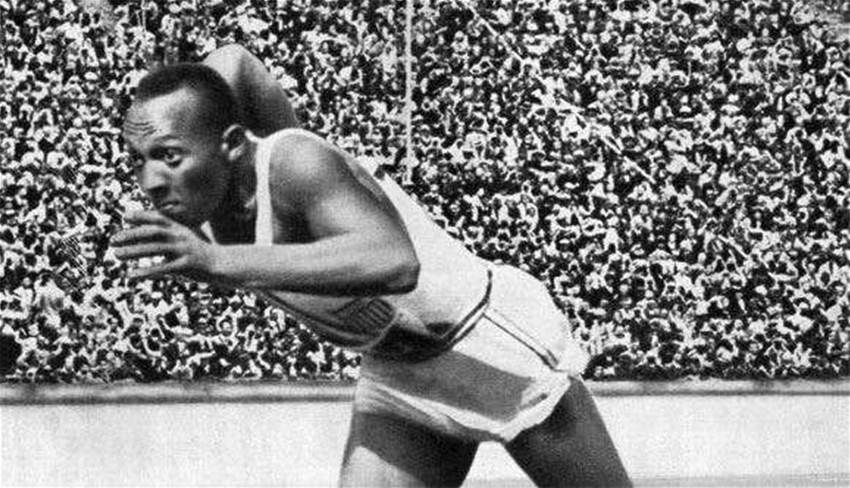

Jesse Owens changed forever any previously-held notions of what was and wasn’t possible for a human to achieve.

photo by Getty Images

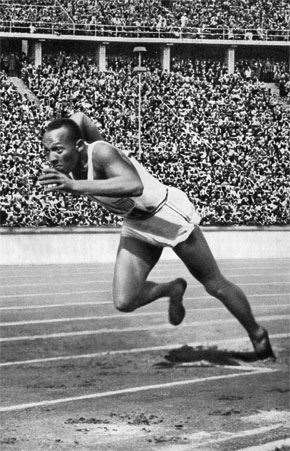

photo by Getty ImagesHe changed forever any previously-held notions of what was and wasn’t possible for a human to achieve.

Jesse Owens wasn’t an innovator for the reasons many might think. He was a pioneer, a pacesetter, simply because he did something no one else up to that time had ever done in sport, and he did it in one hour: he changed forever any previously-held notions of what was and wasn’t possible for a human to achieve.

A self-effacing man, he didn’t make the sort of personal stance against discrimination, war and the abuse of authority that marked the long career of Muhammad Ali. His Olympic Games medals at Berlin in 1936 were entirely expected by those familiar with his capabilities. He was no political hero, despite history’s verdict. He was a man who went to the Berlin Games in 1936 and did what he did best in front of the Fuehrer: he ran and he jumped. In the context of those Games, he became an affront to Hitler’s view of Aryan supremacy; an “up yours” to the Ubermensch. But Owens wasn’t given to making stances. He was a brave, humble man who did his very best. But his best was, of course, magnificent.

No one had previously been able to perform at the very highest level in the world at more than one sport. Yes, there had been incredible multi-disciplinary champions (none more remarkable than last month’s innovator, Jim Thorpe), but to master two and to be an absolute world-beater at both was a feat that had eluded many great athletes.

Owens’ groundbreaking accomplishment took place the year before those Games, in 1935. On that day, during that one-hour span of time, he broke four world records. Well, actually, he tied the fourth, but there was some controversy about the timekeeping for that race.

Think about that: a man exhibited, in front of a relatively modest audience, the pure ability to produce a world record-breaking performance, rest a little, get himself back up to the same heights for another, and another, and another – all during someone’s lunch break. It is, simply, the most amazing hour in the history of track and field athletics – certainly one of the great moments in sport, regardless of the way it has been publicised.

It came while he was a sophomore at Ohio State University. Owens was already an athletic prodigy by this stage, with a tendency to win multiple events. He’d already tied world records in the dash and the broad jump while in high school. That was before coach Larry Snyder identified ‒ and rectified ‒ technical shortfalls in his running style in the sprint and his approach to the pit in the broad jump. World Records

Owens, already a hard-toiling athlete who broke records without a lot of fuss, worked hard to correct the problems, and it all came to a head on May 25, 1935 at Ann Arbour, Michigan. On the day, Owens complained of a severely injured coccyx (tail bone), the result of a playful wrestle with a fellow fraternity member that ended with both of them tumbling down a stairwell. Owens had to be helped in and out of the car by Snyder and team-mates on the way to the meet. He was unable to train all week.

Desperate to alleviate the pain, Owens sat in a hot tub before the meet, and many suggested that he withdraw. He decided to focus on each individual event as though it would be his last. This spelt the end for his competitors. The result of this desperate effort to compete adorns the record books forever.

At those Big Ten Championships, the “Buckeye Bullet”, as he’d come to be known, tied the 100-yard (91.4m) world record, broke the world broad jump record and set new world standards in the 220-yard (201m) dash and the 220-yard low hurdles.

But Owens didn’t just break a bunch of world records. He set standards that would endure. The long jump record (26’-8¼, or 8.13m) would stand for 25 years until famously broken by Bob Beamon in the thin air of Mexico in 1968. With his time of 22.6 seconds on the low hurdles, he became the first man to break the 23-second barrier, and he broke the 200m record in the same run. His record for the 220 yard dash also surpassed the world mark for the 200m. Kenneth L “Tug” Wilson, the Big Ten commissioner, watched in awe: “He is a floating wonder, just like he had wings.”

Nineteen-thirty-five was an amazing year for Owens. He competed in 42 events and didn’t lose one. It was a magnificent achievement, and the next year, due to circumstance, a little fabrication, politics and many agendas, he entered the realm of mythology. History would come to revere the shy sharecropper’s son from Alabama as a symbol for many things. Fans of sport still marvel at that single hour of power.

‒ Robert Drane

Related Articles

Champion A-League coach set to join Premier League giants

Emerging Socceroos star set to sign for MLS club