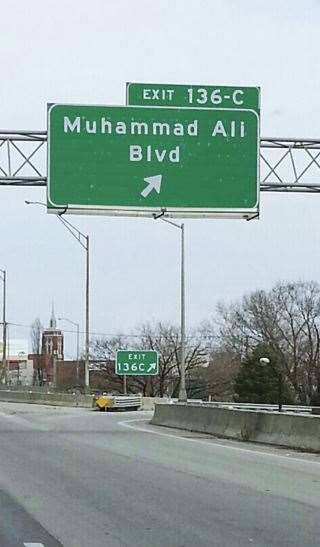

The legend and legacy of Muhammad Ali is right at home in Louisville.

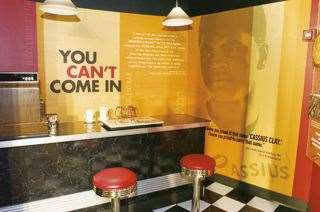

In the epic mythology of Muhammad Ali, the city of Louisville comes off as something of a villain. It’s the den of racism – the very place where the minstrel character Jim Crow was thought to have originated – that drove a young Olympic boxing champion, Cassius Clay, furious at having been denied service at a segregated diner, to toss his gold medal into the Ohio River.

This incident is famously apocryphal. It was immortalised in the 1977 Ali biopic The Greatest, and ended up as another of those anecdotes told about the three-time heavyweight champ. Because when it comes to Ali, printing the legend well and truly won out over telling the technical truth long ago, and maybe that’s only appropriate. Ali is a character too outlandish for fiction to have created, which is perhaps why the literary likes of Norman Mailer and George Plimpton were so transfixed by him.

In the middle of the Ali Centre, the Louisville museum devoted to the man, is a re-creation of that diner counter, a touch of mid-century retro kitsch that sticks out amid the rest of the displays. The stools invite you to sit down – the moment you do, a disembodied and rather unkind voice suddenly pipes in, asking what you’re doing there, boy (emphasis on the “boy”, stretched to two syllables: bo-ah). Open up the menu on the counter, and instead of the chef’s specials, you can read about the complicated history of race in this part of the world.

Louisville is hardly the deep South; Kentucky was a Union state during the Civil War, and as the saying goes, only became Confederate afterward. By its geography, Louisville is as much a Midwestern town as it is Southern – cross the river, and you’re in Indiana. It’s known for being a genteel city – even when segregated, it prided itself on not being harsh about it. What can also be said of Louisville is that it’s a genuine sporting town, a reputation it’s been able to uphold even without a big-league pro team to represent it on the national stage. Churchill Downs, site of the Kentucky Derby, is located here, while the University of Louisville is a long-time power and reigning champ of US college basketball. Walk down the city’s Main Street, and every lamppost and sidewalk bench bears a tribute to the Louisville Slugger bat, which is to baseball what Gray-Nicolls is to cricket.

But for its most famous sporting son – most famous son in general, really – the city reserves a special pride. The Ali Centre was opened in 2005 after more than a decade in development and, tellingly, it ended up in Louisville rather than some tourist walk in Las Vegas or Florida. As grand as the scope of Ali’s life was, encompassing his exploits from Rome to New York to Kinshasa to Manila, and not to mention his dramatic personal reinvention that still looks utterly radical today, he was a parochial figure at heart, a product of where he came from. There’s a moment in Leon Gast’s Oscar-winning documentary, When We Were Kings, when Ali, hyping the upcoming George Foreman fight, describes it as “bigger than Evel Knievel and the Kentucky Derby on the same day”. Who but a Louisville kid would say that?

There’s a strong feeling of homecoming to the Ali Centre, the full circle that puts itself out there as the final word on the Ali legacy. As the narrative goes, he’s come to transcend sport, and now occupies the lower end of the cultural tier reserved for the Gandhis and Mandelas of the world. The museum is organised around “principles”, such as confidence or spirituality, that give off the vaguely new-age glow that’s grown around Ali since the world saw him holding the Olympic torch aloft in Atlanta in 1996. It’s the modern Ali legend, properly cultivated – it even begins with a replica of the 12-year-old Cassius’ red bicycle, the theft of which sent him to the police officer who also happened to run the local boxing gym.

To walk through the impressive detail of the exhibits, however, is to be reminded of something other than heroic destiny – how rambunctiously messy and wilfully out of control Ali’s career often was. The most trenchant of Ali critics, Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram, derided him as a fundamentally naive figure, a pawn who didn’t understand the political forces that were desperate to appropriate him. Kram wrote that Ali had as much social impact as Frank Sinatra, which is to say, not much.

To walk through the impressive detail of the exhibits, however, is to be reminded of something other than heroic destiny – how rambunctiously messy and wilfully out of control Ali’s career often was. The most trenchant of Ali critics, Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram, derided him as a fundamentally naive figure, a pawn who didn’t understand the political forces that were desperate to appropriate him. Kram wrote that Ali had as much social impact as Frank Sinatra, which is to say, not much.

Kram’s view isn’t widely shared, but it does hit on one truth – the young heavyweight champ of the 1960s didn’t know what he was getting himself into. Ali’s refusal to enter the army and the stripping of his title in 1967 became the defining event of his career and his legacy, the moment of conviction that won him admirers everywhere. As you walk from the re-created diner and into a hallway that recounts all the }chaos of the Vietnam War era, you come to appreciate how Ali made his stand. But even accounting for his radicalism, he wasn’t a political figure as much as he had politics thrust upon him.

T he museum, though, is even-handed in its treatment of this topic. A veteran of the Ali circus, American sportswriter Robert Lipsyte, is invoked: “In the beginning, he was enraged at being drafted for selfishly personal reasons; later, he came to understand the outrage of white men sending black men to kill brown men in an unjust war.”

he museum, though, is even-handed in its treatment of this topic. A veteran of the Ali circus, American sportswriter Robert Lipsyte, is invoked: “In the beginning, he was enraged at being drafted for selfishly personal reasons; later, he came to understand the outrage of white men sending black men to kill brown men in an unjust war.”

There’s one other truth that becomes apparent – as respected as he became in the wider culture for being a symbol of resistance, the enduring power of Ali’s story really hinged on his return to boxing, the second act of his career. Where the political Ali can be murky territory, the most genuine part of the man is seen in the ring. Returning to boxing was the most effective statement of social activism Ali could’ve made.

In the central part of the exhibit space is a timeline of Ali’s professional bouts, all 61, from Tunney Hunsaker in Louisville in 1960 to Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas, 21 years later. The accumulated fight record coolly undersells some of the most famous moments in sports history: shocking Liston and the world in ’64; the Fight of the Century against Frazier in ’71; rope-a-doping Foreman in the heart of Africa in ’74; that one, last brutal time against Frazier in the Philippines in ’75. Then there are the interludes that have become forgotten – we know that Ali fought Henry Cooper, George Chuvalo and Joe Bugner, but he actually fought each of them twice. A video bank contains a selection of his fights – you can dial up the 24-year-old champ’s three-round masterpiece over Cleveland Williams in Houston to see a kind of pugilistic perfection. And as Ali generated more good copy for the press than any other athlete in history, it’s appropriate that dispatches from his fights fill out the background. Even the critical Kram, who did some undeniably outstanding work covering the Thrilla in Manila, merits a spot.

The most fun part of the visit is what comes next, a kind of Disney-fied version of Ali’s training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. Deer Lake has a mystique all its own – it was Ali’s pre-fight retreat from 1972, and was known for the various rocks scattered across the property painted with the names of famous fighters. In the museum, it holds various interactive displays, including a speed bag and how-to-box instructional with Ali’s fightin’ daughter, Laila.

The most fun part of the visit is what comes next, a kind of Disney-fied version of Ali’s training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. Deer Lake has a mystique all its own – it was Ali’s pre-fight retreat from 1972, and was known for the various rocks scattered across the property painted with the names of famous fighters. In the museum, it holds various interactive displays, including a speed bag and how-to-box instructional with Ali’s fightin’ daughter, Laila.

Best of all is a heavy bag in the corner, inviting you to put your hands on it. If you don’t brace your feet beforehand, as your correspondent found out, you could be knocked clean over. The bag is attached to a hydraulic of some sort, which simulates the force of a heavyweight’s blow. This immediately calls to mind the way Foreman would pound a melon-sized dent in the heavy bag while his diminutive trainer, Dick Sadler, held on for dear life – and there’s a picture of them on the wall behind. Short of spending actual time in the ring, it’s hard to think of a better insight into what elite boxers are dealing with when the other guy connects.

It’s hard not to feel some guilt about this, to glimpse the fundamental brutality of the fight game and connect it to the present state of Muhammad Ali. The irony has been often remarked upon – that the Louisville Lip has been silenced in his old age. Some have even noted that this was, perhaps, for the best, as Ali himself was given to making outrageously offensive statements. In a politically correct age, his sainted image probably wouldn’t have been able to survive his mouth.

Then again, there was always the Ali charisma, and it should never be underrated. As his corner doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, said, Ali loved people, loved being around people, and seemingly everybody who randomly came into his orbit would leave with a story to tell. There’s a photo tucked away in the corner of the main exhibit floor, recalling an incident in 1981 in Los Angeles. At one end of the frame, a suicidal young man is standing on the ledge of a building. At the other end is a distinctly recognisable Ali, leaning out a window and trying to talk the troubled youth down, which he eventually did. If it wasn’t captured on film, this could’ve been yet another of those tall tales about Ali, right alongside that medal-in-the-river one.

Then again, there was always the Ali charisma, and it should never be underrated. As his corner doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, said, Ali loved people, loved being around people, and seemingly everybody who randomly came into his orbit would leave with a story to tell. There’s a photo tucked away in the corner of the main exhibit floor, recalling an incident in 1981 in Los Angeles. At one end of the frame, a suicidal young man is standing on the ledge of a building. At the other end is a distinctly recognisable Ali, leaning out a window and trying to talk the troubled youth down, which he eventually did. If it wasn’t captured on film, this could’ve been yet another of those tall tales about Ali, right alongside that medal-in-the-river one.

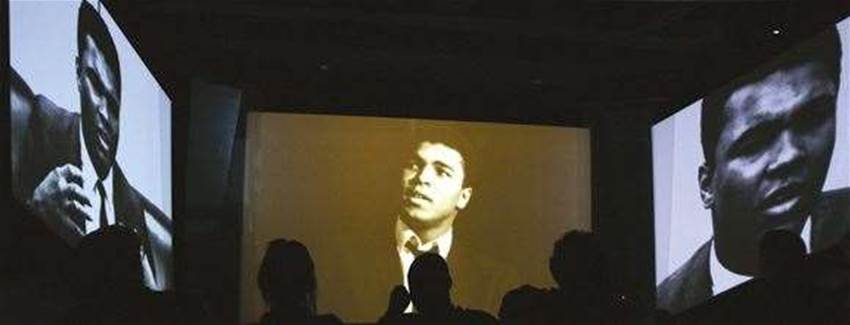

As the Will Smith film of a few years back found out, the person who speaks best for Muhammad Ali is Muhammad Ali. There’s an abundance of archival footage on display, and it radiates with the charm and vivacity that all those would-be successors to Ali’s mantle simply do not possess. Perhaps the most apt description of Ali, cutting through the ambiguities of 1960s politics, the morality of boxing and the general nostalgia about him, is that he was truly an original. And in his place of origin, that essence is being safely preserved. In one film clip, on the way out of the Ali Centre, the champ proclaims in typically effusive style: “I want the world to know that Louisville, Kentucky produces the greatest of all time.” It surely does.

– Jeff Centenera

Main (page 1) photo by Jeff Centenera other photos by Getty Images

Related Articles

Champion A-League coach set to join Premier League giants

Split decision: Popovic in mix as Hajduk hunt new boss