He’s proved himself one of football’s hottest properties, prompting a bizarre tug of war between West Ham, Man United and his agent. FourFourTwo went in search of Carlos Tevez’s secrets.

Page 1 of 3 | Single page

When “Carlitos” Tevez signed for West Ham United at the 11th hour of the transfer deadline in August 2006, we knew we were in for some story…

Up until that minute rumours were rife that the small Argentinian forward would join a Premiership club, but the names touted were the big four – apt stages for an international who had stunned the world with his flair during the World Cup.

Stocky and bull-like, with the sort of skills and ball control the world has come to associate with Argentina, Tevez had been a regular in his national team’s famous youth squad, picking up World trophies and Olympic medals alike. He spent a season with Brazilian club Corinthians, where in spite of an abrupt and antagonistic departure he became an idol and won the domestic league.

During the World Cup in 2006, Argentina were knocked out by Germany – but for lovers of “beautiful” football, they were the team who displayed the most breathtaking technique. And Tevez shone. Arguably even against Germany, he demonstrated an ability to both showboat and play with efficiency, displaying individual flair and assisting the team – and to charge with rhythm and play until the 90th minute with the same stamina as the first.

In a restaurant in Hamburg after the match against Holland, a cluster of international football agents were dining. “Tevez will join the Premiership next season,” they were tipping reporters, “but only for $100 million.”

So when West Ham unveiled their new signing – part of a double coup along with fellow Argentinian, midfielder Javier Mascherano, also from Corinthians – with the proviso that an undisclosed deal had secured both top internationals for a very modest fee, speculation started in earnest about what might be going on behind the scenes.

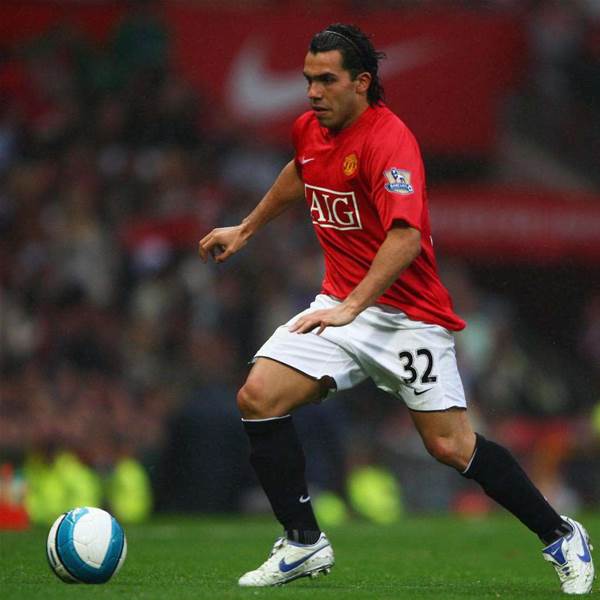

Argentina’s squad was in London at the time, for a friendly against Brazil. The jaw-dropping transfer was announced to the press in an East End hotel. Tevez sank low into a deep leather armchair and joked about how the only thing he knew about West Ham was that the club’s insignia consisted of two little hammers. Someone asked him if he had a shirt yet. He didn’t, so someone else made a point of seeking a blue and claret strip, returned with it already bearing the number 32, and Tevez hugged them with joy. Why 32? “Michael Jordan. I’ve always loved him and the 23 or 32 evoke him for me,” he said. Just like David Beckham, FourFourTwo ventured. It was obvious from the reaction around us that this wasn’t taken as a compliment.

The preferred analogy on the day was that of Diego Maradona’s joining Napoli; a small, forgotten club with a long tradition of football-loving supporters who loyally stuck by them through times of trouble; a club with a history. A club in need of a number 10 groomed in the vacant lots of Buenos Aires’s poorer quarters.

In the beginning, West Ham fans rejoiced and Alan Pardew, then manager, spoke candidly about his delight and his reluctance to question the hand that fed him. The deal, confused and confusing, was incomprehensible from a business perspective. But Pardew was providing soundbites about how brilliant it was to have “world-class players,” and all seemed set to roll along smoothly for West Ham, who were emerging from a spectacular season, to continue enjoying lashings of glory.

The remains of the summer were still just perceptible at the training ground in those days, with early-morning Friday press conferences in the sunshine and Tevez bouncing about trying to find his feet in his new home. During training, Pardew’s voice could be heard commending him as the newcomer dribbled his way across the fields of Chadwell Heath.

There was something so quintessentially English about the surroundings, the gates into the training ground, the neat rows of cars, the timetables and contempt for Argentinian improvisation among the press. But the players kept high spirits and showed enthusiasm for their new life. “We want to be here for a very long time,” they said.

As the clocks changed and winter set in, it was more than the skies that darkened. Pardew didn’t seem able to find a way to accommodate his “world-class players”, and both often found themselves on the bench. The drizzle and the cold came hand in hand with a run of bad results. Increasingly, observers questioned what these two Argentinians were doing at West Ham. Alfio Basile, appointed manager of Argentina’s squad, told a press conference that he watched them “and they worried him”.

Basile’s comments were based on tactics and football styles. In particular, he expressed concern about Mascherano, a typical number five in the Argentinian sense of the word, not being exploited to capacity.

“I like Mascherano as a double five,” Basile had said, using a phrase that refers to the South American tactic of playing two holding midfielders one in front of the other. Obviously it wasn’t simply a matter of numbers and translations hampering the Argentinian’s fortunes. But perhaps there was an untranslatable quality to the way they play, the vocabulary they use to define and describe it, the codes on and off the pitch.

Another example is the word gambeta, as used in Argentina. Gambeta can be described as the combination of dribbles and feints used by the most dazzling players, but it is actually much more. In a sense, it is the aim and purpose of the kid who plays for fun. When asked to define it in English, former Real Madrid sporting director Jorge Valdano said: “It’s like a tango – only different.”

Carlos Tevez, on the other hand, is more to the point, his language lacking such frills: “It’s getting a guy off your back while keeping the ball at your feet,” he once told me. Such a prosaic definition does Tevez no justice, though. What he can do when he gets hold of the ball is more akin, as the Argentinian rock song The Dance of the Gambeta goes, to the rather more poetic “dribbling fate”. As Basile had said, Tevez can play all over the pitch (but not on the left). Rather than a straightforward striker, he is more of an Argentinian number 10 – a link, a thinker, a playmaker. But he has the speed and strength of the young Ronaldo (the Brazilian) as well as the precision and efficiency of the unfussy pragmatist.

Ciaran Simpson, who worked with him at West Ham as his translator, said: “If he loses the ball in a trick, he will run 120 metres to recover it.” His skills are unparalleled, and although rarely displayed gratuitously, are full of the charm and attention to detail so often associated with the street children of South America.

Up until that minute rumours were rife that the small Argentinian forward would join a Premiership club, but the names touted were the big four – apt stages for an international who had stunned the world with his flair during the World Cup.

Stocky and bull-like, with the sort of skills and ball control the world has come to associate with Argentina, Tevez had been a regular in his national team’s famous youth squad, picking up World trophies and Olympic medals alike. He spent a season with Brazilian club Corinthians, where in spite of an abrupt and antagonistic departure he became an idol and won the domestic league.

During the World Cup in 2006, Argentina were knocked out by Germany – but for lovers of “beautiful” football, they were the team who displayed the most breathtaking technique. And Tevez shone. Arguably even against Germany, he demonstrated an ability to both showboat and play with efficiency, displaying individual flair and assisting the team – and to charge with rhythm and play until the 90th minute with the same stamina as the first.

In a restaurant in Hamburg after the match against Holland, a cluster of international football agents were dining. “Tevez will join the Premiership next season,” they were tipping reporters, “but only for $100 million.”

So when West Ham unveiled their new signing – part of a double coup along with fellow Argentinian, midfielder Javier Mascherano, also from Corinthians – with the proviso that an undisclosed deal had secured both top internationals for a very modest fee, speculation started in earnest about what might be going on behind the scenes.

Argentina’s squad was in London at the time, for a friendly against Brazil. The jaw-dropping transfer was announced to the press in an East End hotel. Tevez sank low into a deep leather armchair and joked about how the only thing he knew about West Ham was that the club’s insignia consisted of two little hammers. Someone asked him if he had a shirt yet. He didn’t, so someone else made a point of seeking a blue and claret strip, returned with it already bearing the number 32, and Tevez hugged them with joy. Why 32? “Michael Jordan. I’ve always loved him and the 23 or 32 evoke him for me,” he said. Just like David Beckham, FourFourTwo ventured. It was obvious from the reaction around us that this wasn’t taken as a compliment.

The preferred analogy on the day was that of Diego Maradona’s joining Napoli; a small, forgotten club with a long tradition of football-loving supporters who loyally stuck by them through times of trouble; a club with a history. A club in need of a number 10 groomed in the vacant lots of Buenos Aires’s poorer quarters.

In the beginning, West Ham fans rejoiced and Alan Pardew, then manager, spoke candidly about his delight and his reluctance to question the hand that fed him. The deal, confused and confusing, was incomprehensible from a business perspective. But Pardew was providing soundbites about how brilliant it was to have “world-class players,” and all seemed set to roll along smoothly for West Ham, who were emerging from a spectacular season, to continue enjoying lashings of glory.

The remains of the summer were still just perceptible at the training ground in those days, with early-morning Friday press conferences in the sunshine and Tevez bouncing about trying to find his feet in his new home. During training, Pardew’s voice could be heard commending him as the newcomer dribbled his way across the fields of Chadwell Heath.

There was something so quintessentially English about the surroundings, the gates into the training ground, the neat rows of cars, the timetables and contempt for Argentinian improvisation among the press. But the players kept high spirits and showed enthusiasm for their new life. “We want to be here for a very long time,” they said.

As the clocks changed and winter set in, it was more than the skies that darkened. Pardew didn’t seem able to find a way to accommodate his “world-class players”, and both often found themselves on the bench. The drizzle and the cold came hand in hand with a run of bad results. Increasingly, observers questioned what these two Argentinians were doing at West Ham. Alfio Basile, appointed manager of Argentina’s squad, told a press conference that he watched them “and they worried him”.

Basile’s comments were based on tactics and football styles. In particular, he expressed concern about Mascherano, a typical number five in the Argentinian sense of the word, not being exploited to capacity.

“I like Mascherano as a double five,” Basile had said, using a phrase that refers to the South American tactic of playing two holding midfielders one in front of the other. Obviously it wasn’t simply a matter of numbers and translations hampering the Argentinian’s fortunes. But perhaps there was an untranslatable quality to the way they play, the vocabulary they use to define and describe it, the codes on and off the pitch.

Another example is the word gambeta, as used in Argentina. Gambeta can be described as the combination of dribbles and feints used by the most dazzling players, but it is actually much more. In a sense, it is the aim and purpose of the kid who plays for fun. When asked to define it in English, former Real Madrid sporting director Jorge Valdano said: “It’s like a tango – only different.”

Carlos Tevez, on the other hand, is more to the point, his language lacking such frills: “It’s getting a guy off your back while keeping the ball at your feet,” he once told me. Such a prosaic definition does Tevez no justice, though. What he can do when he gets hold of the ball is more akin, as the Argentinian rock song The Dance of the Gambeta goes, to the rather more poetic “dribbling fate”. As Basile had said, Tevez can play all over the pitch (but not on the left). Rather than a straightforward striker, he is more of an Argentinian number 10 – a link, a thinker, a playmaker. But he has the speed and strength of the young Ronaldo (the Brazilian) as well as the precision and efficiency of the unfussy pragmatist.

Ciaran Simpson, who worked with him at West Ham as his translator, said: “If he loses the ball in a trick, he will run 120 metres to recover it.” His skills are unparalleled, and although rarely displayed gratuitously, are full of the charm and attention to detail so often associated with the street children of South America.

Related Articles

Socceroos coach says Argentina can only 'play two ways'

Argentina coach on 'inferior' Socceroos: 'I don't fully agree'