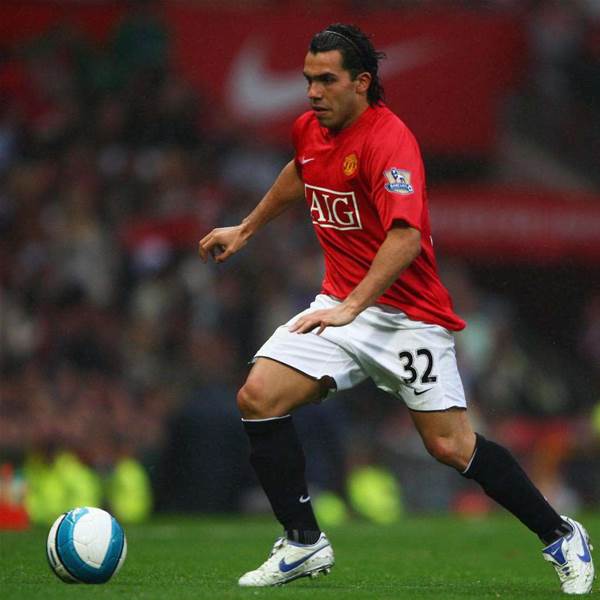

He’s proved himself one of football’s hottest properties, prompting a bizarre tug of war between West Ham, Man United and his agent. FourFourTwo went in search of Carlos Tevez’s secrets.

Page 2 of 3 | Single page

Carlos Tevez was raised in Fuerte Apache (Fort Apache), an astonishingly poor area of Buenos Aires afflicted with a huge crime rate. Tevez has been frank about the difficult childhood he had there, and has been quoted saying that despite the fact that they often didn’t have enough to eat, he feels proud of the place where he was born and raised.

In his case, however, the harsh realities of Fuerte Apache didn’t quash the dream. He was very good at football and his talent was spotted early on. He would play with much older kids for the fun of it – even when they played for money. He was signed by Boca in 1997, and the hunger that drove him in the informal kickarounds never left him. Under the tutelage of Ruben Madonni at club level and Jose Pekerman at international level, by 1999 he was representing Argentina at Wembley.

It was a three-way under-16 friendly tournament between England, France and Argentina. Argentina sent a squad of 14-year-olds because Jose Pekerman and Hugo Tocalli, the head of youth development, felt it would be a good introduction for them: how to behave in a hotel, how things work in other countries, a taste of the facilities at a training ground… Most of those boys had never even been on a plane before; many had never set foot outside Argentina.

Tocalli let me travel to Wembley in the coach with the kids, and then sit on the bench. As the coach drove into what was then the world’s football cathedral, one of boys stood with his mouth wide open: “What the fuck are we doing here!?” he gasped. They took on their English opponents – a couple of years older and several inches taller – nervously but bravely. Before the game, we had asked Tocalli which one of them we should look out for in years to come. Was there one who would definitely make it? Without hesitation he had pointed to a small, stocky, cheeky clown joking about with a ball. A boy with

a noticeable scar running along the side of his face, all the way down his neck and torso: Carlos Tevez. Tevez scored at Wembley. “That was my first goal in the Argentina strip,” he tells FourFourTwo his eyes full of delight at the memory.

On June 5, he scored again in an Argentina friendly, this time a confident header from a pass by Messi; this time one of the most established names in the squad, one of the most experienced members of the team, and one of the few dead certs for this year’s Copa America squad. But on the pitch he does not look any different from back then.

Tevez’s debut for Boca’s first team came a few years later, and he quickly became the club’s idol. Following in the footsteps of Maradona and Riquelme, both of whom befriended and supported him – and shared his experience of an extremely deprived childhood – Tevez embodied the typical tale of the boy from the neighbourhood for whom football becomes the meal ticket out of the slum. He gave everything, playing every game as if it really mattered. He still does.

He became a celebrity quickly too; a controversial one. Media interest in his private life became intrusive, the paparazzi never left his side, and by the time Boca sold him to Brazilian club Corinthians, he expressed relief at the distance he would gain from Argentina’s national press. In Brazil, he said, they were more interested in what he did on the pitch than off it.

But by the time he left Corinthians, controversy had caught up with him again. Appearing at a press conference wearing a Manchester United strip, a physical fracas with opposing fans, and a heated exchange with the manager all contributed to his departure being a little rushed. Some even described it as a flight. Nevertheless, his potent play had by then helped the club win the league. And for this, Tevez became an hero to the fans.

The murky world of international transfers is never clear at the best of times. In South America, where clubs are more often broke than not, and therefore unable to afford top players, it’s common for third parties to become involved in the financing of players. So, trust funds are set up, where investors contribute to the purchase of players in the hope of recouping their money with subsequent sales. Sometimes, instead of trust funds, individuals finance the players. Particularly in Argentina, where private ownership of clubs is prohibited by law and many aspects of club management are contracted out to third parties, what is commonly described as “player ownership” is not uncommon.

Mauricio Macri, chairman of Boca Juniors, sold Tevez to Corinthians. He told FourFourTwo it was a straightforward transaction in which he insisted the full amount be paid up front. Corinthians were by then under the management of MSI, an international company fronted by an Iranian, Kia Joorbachian.

Joorbachian had also expressed an interest in buying West Ham, and a serious offer was under consideration when he moved Tevez and Mascherano to the East End. The idea was to build a team around them, and the fact that the “sale” had not been for as much as was touted during the summer was not a problem so long as the long-term vision worked.

Enter Eggert Magnusson, an Icelandic football man and businessman. “I’ve been following English football for 50 years,” he told journalists in his first briefing after he took over the club. Magnusson’s consortium bought West Ham, quite suddenly, having outbid Joorbachian.

One of the first things Magnusson said when he arrived at Upton Park, was that he was unhappy with the contracts for the two Argentinians; this notion of them being owned and loaned, or partly owned, by a consortium. “Would he have entered into the agreement?” someone asked. “No.”

It’s still unclear what the terms of this agreement are, and the affair has had an additional spanner thrown into its works by the FA’s decision to fine West Ham for breach of rules. The FA does not allow third-party ownership of, or third parties to benefit from the sale of players. Deals must be club to club. This complicates many South American transfers, where the “selling” club is not always the outright “owner” of the player. In the UK, however, the situation is somewhat stricter: a player must be registered with a federation, that registration must be lodged with a club, and that club in turn must have some sort of contractual agreement with the player.

In his case, however, the harsh realities of Fuerte Apache didn’t quash the dream. He was very good at football and his talent was spotted early on. He would play with much older kids for the fun of it – even when they played for money. He was signed by Boca in 1997, and the hunger that drove him in the informal kickarounds never left him. Under the tutelage of Ruben Madonni at club level and Jose Pekerman at international level, by 1999 he was representing Argentina at Wembley.

It was a three-way under-16 friendly tournament between England, France and Argentina. Argentina sent a squad of 14-year-olds because Jose Pekerman and Hugo Tocalli, the head of youth development, felt it would be a good introduction for them: how to behave in a hotel, how things work in other countries, a taste of the facilities at a training ground… Most of those boys had never even been on a plane before; many had never set foot outside Argentina.

Tocalli let me travel to Wembley in the coach with the kids, and then sit on the bench. As the coach drove into what was then the world’s football cathedral, one of boys stood with his mouth wide open: “What the fuck are we doing here!?” he gasped. They took on their English opponents – a couple of years older and several inches taller – nervously but bravely. Before the game, we had asked Tocalli which one of them we should look out for in years to come. Was there one who would definitely make it? Without hesitation he had pointed to a small, stocky, cheeky clown joking about with a ball. A boy with

a noticeable scar running along the side of his face, all the way down his neck and torso: Carlos Tevez. Tevez scored at Wembley. “That was my first goal in the Argentina strip,” he tells FourFourTwo his eyes full of delight at the memory.

On June 5, he scored again in an Argentina friendly, this time a confident header from a pass by Messi; this time one of the most established names in the squad, one of the most experienced members of the team, and one of the few dead certs for this year’s Copa America squad. But on the pitch he does not look any different from back then.

Tevez’s debut for Boca’s first team came a few years later, and he quickly became the club’s idol. Following in the footsteps of Maradona and Riquelme, both of whom befriended and supported him – and shared his experience of an extremely deprived childhood – Tevez embodied the typical tale of the boy from the neighbourhood for whom football becomes the meal ticket out of the slum. He gave everything, playing every game as if it really mattered. He still does.

He became a celebrity quickly too; a controversial one. Media interest in his private life became intrusive, the paparazzi never left his side, and by the time Boca sold him to Brazilian club Corinthians, he expressed relief at the distance he would gain from Argentina’s national press. In Brazil, he said, they were more interested in what he did on the pitch than off it.

But by the time he left Corinthians, controversy had caught up with him again. Appearing at a press conference wearing a Manchester United strip, a physical fracas with opposing fans, and a heated exchange with the manager all contributed to his departure being a little rushed. Some even described it as a flight. Nevertheless, his potent play had by then helped the club win the league. And for this, Tevez became an hero to the fans.

The murky world of international transfers is never clear at the best of times. In South America, where clubs are more often broke than not, and therefore unable to afford top players, it’s common for third parties to become involved in the financing of players. So, trust funds are set up, where investors contribute to the purchase of players in the hope of recouping their money with subsequent sales. Sometimes, instead of trust funds, individuals finance the players. Particularly in Argentina, where private ownership of clubs is prohibited by law and many aspects of club management are contracted out to third parties, what is commonly described as “player ownership” is not uncommon.

Mauricio Macri, chairman of Boca Juniors, sold Tevez to Corinthians. He told FourFourTwo it was a straightforward transaction in which he insisted the full amount be paid up front. Corinthians were by then under the management of MSI, an international company fronted by an Iranian, Kia Joorbachian.

Joorbachian had also expressed an interest in buying West Ham, and a serious offer was under consideration when he moved Tevez and Mascherano to the East End. The idea was to build a team around them, and the fact that the “sale” had not been for as much as was touted during the summer was not a problem so long as the long-term vision worked.

Enter Eggert Magnusson, an Icelandic football man and businessman. “I’ve been following English football for 50 years,” he told journalists in his first briefing after he took over the club. Magnusson’s consortium bought West Ham, quite suddenly, having outbid Joorbachian.

One of the first things Magnusson said when he arrived at Upton Park, was that he was unhappy with the contracts for the two Argentinians; this notion of them being owned and loaned, or partly owned, by a consortium. “Would he have entered into the agreement?” someone asked. “No.”

It’s still unclear what the terms of this agreement are, and the affair has had an additional spanner thrown into its works by the FA’s decision to fine West Ham for breach of rules. The FA does not allow third-party ownership of, or third parties to benefit from the sale of players. Deals must be club to club. This complicates many South American transfers, where the “selling” club is not always the outright “owner” of the player. In the UK, however, the situation is somewhat stricter: a player must be registered with a federation, that registration must be lodged with a club, and that club in turn must have some sort of contractual agreement with the player.

Related Articles

Socceroos coach says Argentina can only 'play two ways'

Argentina coach on 'inferior' Socceroos: 'I don't fully agree'