James Smith recently caught up with Johnson at a Jim Beam Racing promo day at Eastern Creek and tried his best not to appear too starstruck.

James Smith recently caught up with Johnson at a Jim Beam Racing promo day at Eastern Creek and tried his best not to appear too starstruck.

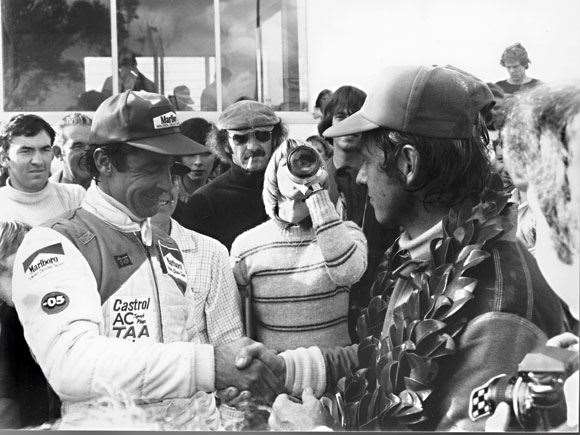

“When you beat Brocky, you knew damn well you’d just beaten one of the best. Image: Chevron Library

“When you beat Brocky, you knew damn well you’d just beaten one of the best. Image: Chevron LibraryMost significantly, though, “Tricky Dicky” was a thrill-seeking flag-waver for battlers Australia-wide. He was their man. In 1980 his disciples donated tens of thousands to get his Tru Blu XD Falcon back on track after he hit a boulder that had rolled onto the Mt Panorama circuit while “DJ” led the Great Race. “The rock” ended his day, but the support he received kick-started the career of one of the true legends of Australian sport. He took just a year to repay the faith, winning the Bathurst 1000 for the first time in ’81.His two other famous Bathurst victories, five Australian Touring Car Championships and spectacular crashes complete one hell of a highlights reel of a career which ended in retirement in 1999. Johnson’s still very much involved with V8 Supercar team Jim Beam Racing (or DJR), which boasts his son Steven and star recruit James Courtney. James Smith recently caught up with Johnson at a Jim Beam Racing promo day at Eastern Creek and tried his best not to appear too starstruck.

Who was responsible for kicking off the driving life of Dick Johnson?

“My Dad used to get me up at 4.30 every morning for swimming training down at the Valley Baths in Brisbane. We lived at Coorparoo, about a 15km drive away. He had ambitions of me being an Olympic swimmer and I did extremely well at it. But at the end of the day, the only way he could get me to train was if he let me drive the car from home down to the pool. I was eight years of age. I don’t just mean sitting on his lap holding the steering wheel … I was in the driver’s seat, he was sitting next to me, my two sisters in the back. He obviously saw what my real passion was.”

Today’s professional V8 Supercar stage must seem very foreign to your early

big-time racing days ...

“When I first got involved it was very much an amateur sport. There was no professionalism at all. You certainly couldn’t have sponsors. Back then, the car that I used to race was the one I used to drive to work everyday. “Being forever pulled up by the police or the transport department – who never liked people modifying cars from their original manufacturer’s specifications – made me realise I needed two vehicles, one to tow the car and one to race, but I could never afford it. The only way I could fund it was to be self-employed, which I was, after I did two year’s national service. “I thought, ‘How am I going to find the money?’ hoping I’d find a bird who had a car! This is where I met my wife, Jill … but not in that order, of course. The vehicle she had at that point was a Mini, which was totally unsuitable for towing anything, especially a Holden on a trailer. So I convinced her she had to sell that and buy a bigger, more powerful car, which she did … There was our tow car. Then we were on the road, as they say, and we’re still on the road 30-odd years later.”

Is there any discipline or category of racing you never competed in?

“I’ve never ever driven an open-wheel car, other than a Model A historic car which I drove in a hill climb, which you wouldn’t exactly say is conquering the open-wheel brigade.“It was something I promised my mother I’d never do ... other than go-karts, of course – I took those up when I had a bit of a lull in my career. On occasions you’d end up with a helmet, a pair of gloves and race suit and nothing to sit in. That’s when I was driving other people’s vehicles.”

Victory was sweet for “Tricky Dicky” and John French a year later ... Image: Getty Images

Victory was sweet for “Tricky Dicky” and John French a year later ... Image: Getty ImagesLooking back, what were your best qualities as a race driver?

“One of the best qualities I had was being compassionate about what parts of the car were vulnerable … The brakes – for the weight of the car – were very small and inadequate, for example. Over a long distance you had to really look after the brakes so you’d finish the race. Something my Dad always taught me was ‘to finish first, first you must finish’. That was always in the back of my mind. I was very kind to the car in many ways.“It was also a matter of being self-critical without being stupid. The one thing I never ever did was feed off the bullshit, the media hype. I knew what I could achieve and what I couldn’t achieve, and I never stepped over that line.”

What’s it like rounding a blind right-hander at Bathurst, finding a tow truck in your way, trying to avoid it, only to smack into a boulder sitting in the middle of the track (1980)? Did you ever find out how “the rock” got there?

“It’s the best worst thing that ever happened to me. I can honestly say I know exactly how it got there. About 12-18 months ago – I still have the email – this guy, who was a resident of Mt Panorama at the time, wrote to me. That day, he and his wife were sitting on the hill where it happened. There were no spectators within 50m either side of them. He said these two other guys, who had obviously been out all night and were feeling a little bit average, were walking up past them and the only reason they noticed them was the fact that out of everywhere they could’ve gone, they sat down right in front of these two people. One of them laid down with his feet resting on a rock – which was about the size of a soccer ball – and unfortunately he dislodged it, it rolled down the hill and fell onto the race track. In his email he said once this had happened, the two blokes took off at 100 miles an hour. It was never intentional, and I never thought for a moment it was.”

The support you received from fans immediately after was amazing, right?

“At the time, flashing before my eyes was, ‘I’ve mortgaged the house, I’ve screwed up … ’ But as the day unfolded, with Channel Seven being inundated with calls on their switchboard from people wanting to donate money and help, I thought, ‘This is really starting to turn into a positive here.’ After so many years of trying to get into the big-time, this was our opportunity. It was the most humbling experience you could ever imagine. You get to the point where you think, ‘Gee, a lot of people do care.’ The next 12 months were probably the toughest I’ve ever had and the most pressure I’ve ever felt, having gained the support of all those people, including Ford Australia, who matched everything dollar for dollar. The mail van used to back up to the house with bags and bags of letters, which was incredible.” (Johnson won the race the following year.)

Should the popular V8 curtain-raiser to the F1 Grand Prix at Albert Park be included in the championship?

“Absolutely, but we need to be able to use a separate pit area somewhere where we can operate like we do at other race meetings. There’s no way we can have a proper race meeting and be part of the F1 circus in the conditions we have currently. The thing that really kills us is the facilities in pit lane. It’s that tight, it’s almost dangerous.There’s no way we could do pitstops – it would be a nightmare.”

You raced in NASCAR for a short time. What are your thoughts on Marcos Ambrose’s prospects in the US?

“He’s really starting to get the gist of the game. NASCAR is completely different to our type of racing. It’s a different discipline to understand how to handle an oval track. The types of car – even though they physically look similar to ours; the size of the wheels and tyres and the overall weight – are completely different. It becomes very difficult for someone to adapt to that. It’s more of a speedway background than a circuit background. Marcos has done a remarkable job. He’s really starting to earn his place. He’s finishing in good positions quite often. He’s got the ability to do it, it’s just a matter of adapting to it all and working with people he hasn’t worked with before.”

How do you rate Dick Johnson as an everyday, regular road user?

“I’m very mindful of what’s happening around me. I probably concentrate as much on the road as what I used to on the race track. I get very disappointed in people who have no idea of what they’re doing or what’s happening around them. You can see they’re going to have an accident before they have it. I can read the road surface … I can drive along freeways, anywhere you like, and I can tell you with a 90 per cent success rate exactly what every person’s going to do before they do it. And that’s what driving’s all about. You have to anticipate what other drivers are going to do, so you’re not surprised by their moves or when they change lanes. This is what I tell kids.”

Johnson and DJR recruit James Courtney. Image: Getty Images

Johnson and DJR recruit James Courtney. Image: Getty ImagesWhich road rule really annoys you?

“There’s one that no one ever takes any notice of: keep left unless overtaking. These dills who drive around in the right-hand lane under the speed limit, all they’re doing is frustrating everyone behind them – most of them don’t know what they’re doing anyway. If you’re not passing someone, why be out there? “There’s only one solution that will fix the road toll, and it’s not going to be an overnight solution. It’s a generational thing. Unless we teach people how to drive, we’re never ever going to win. We’re not teaching people how to drive, we’re teaching them how to acquire a license. The education system should start at eight years of age with the theoretical side, and going right through to 14, where they should be sitting behind the steering wheel of a car in a controlled situation to be able to know what to expect next.”

Peter Brock’s death in 2006 must’ve had an immense impact on you. What’s your best memory of him?

“Not only the fact he was an excellent driver and he was a very tenacious sort of a guy, but the fact he was a really fair racer. The great testament to that would’ve been at Lakeside in 1981, which was the last round of the championship. We were one point apart, so whoever beat who was going to be the champion. We were on the front row together, and for the whole race we were never more than a car-length apart. There were any number of times where he could’ve punted me off the road, but he didn’t because he was a fair racer. If he couldn’t beat me fair and square, he wasn’t going to beat me. We finished a car-length apart and I won the championship.“When you beat ‘Brocky’, you knew damn well you’d beaten one of the best. At the end of the day, we never stooped to foul play to come out on top. All the years we raced together, wheel to wheel, side by side, we never ever swapped paint.”

You were such serious rivals, but did you actually like each other?

“We used to get on really well, but once we put our helmets on and got out on the race track, we were two totally different people again. There was always the fun side of it, but we knew when that stopped. We wouldn’t give each other an inch.”

We nearly lost you in 1983 when you exited Forrest’s Elbow on your top-ten shootout lap. How did you fit through those trees? (See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ektTw5lpoyY)

“I remember thinking, ‘I could be in a bit of trouble here.’ I went through the trees and I’d stopped and thought, ‘Thank God for that.’ I can’t remember anything from getting out of the car to the time I was walking up the back of the pits with my wife and John French, who was partnering me in my car, and his wife. Maybe that’s because, when I was sitting at the top of the hill, the next car around was the final car to contest the top-ten shootout, and it was Peter Brock. He stopped and gave me a lift back to the pits and maybe that’s why I’ve forgotten. That’s the sort of relationship we had with Brocky in those situations and I would’ve done the same thing for him … I’m sure he would’ve forgot something like who’d given him a lift, too.”

– James Smith

Related Articles

.jpeg&h=172&w=306&c=1&s=1)

Langerak to bolster Victory's ALM title bid in January

Socceroo-in-waiting seals Championship deal