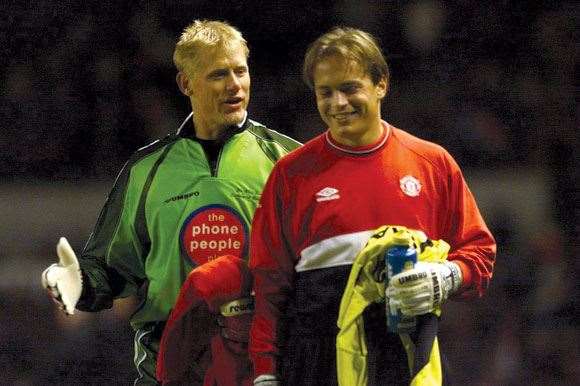

Bosnich was considered by more than a few authorities at one point as the finest goalkeeper in the world

photo by Getty Images

photo by Getty ImagesBosnich was considered by more than a few authorities at one point as the finest goalkeeper in the world

Suffice to say, Mark Bosnich’s name is used to being in a headline. Throughout his soccer career, Bosnich was a magnet for the big, bold print: the Nazi salute to the Tottenham Hotspur fans, the orgy video at Dwight Yorke’s house, the tempestuous tabloid relationship with British model Sophie Anderton, the subsequent descent into cocaine addiction that saw him become the first English Premier League player to be banned for drugs, and almost led him to shoot his father with an airgun.

The salacious stuff largely obscures another significant detail – Bosnich was considered by more than a few authorities at one point as the finest goalkeeper in the world, a status which landed him as the first name on an all-conquering Manchester United’s team sheet in 1999. Decline followed quickly, and repeated attempts at a comeback both in England and Australia never stuck.

Bosnich, however, has found his place within the game again, remaking himself into a highly effective presence on Fox Sports’ soccer programming. There was always an inkling that Bozza’s qualities would make for great television – he’s lively, raffish and genuinely insightful, gained from hard-earned experience, although often in need of tempering. His run sheet for an upcoming A-League match includes a note from his producer: “No soliloquies!” When he sat down with Inside Sport, we did no such thing to hold Bosnich back from holding forth.

First, a question about goalkeepers: by definition, because of the job they have to do, the pressure and attention that’s on them, do they generally have unusual personalities?

The vast majority of goalkeepers will be remembered for their mistakes rather than for their glories. When you do something glorious, the majority of people turn around and go, “That’s what you’re paid for.” When you make a mistake: “What are you doing?”

I say it’s a different type of personality. You’ve got to be able to take all that upon yourself and also have the ability to do nothing throughout a game, and be called upon for that split second and make a save that could make or break your side.

What’s the weirdest goalkeeper superstition or ritual you’ve seen?

Not a goalkeeper – I remember Steve Bruce at Man United, I only played with him a couple of times when I was a young pup. He had to go to the toilet before he went out. Some other players, who shall remain nameless, would have one of those tiny hotel bottles, a sip of brandy to calm their nerves.

I’ve seen players who were that nervous they were physically sick before a game or even at half-time. There was a great story when I was at Villa, I don’t want to name the guy because it’s embarrassing. We were having a team talk with Brian Little, and Brian’s going, “You’re doing really well today, boys, just keep it going.” And in the background, you hear [cue throwing up noise]. So everybody handles that type of pressure differently.

Me personally, my only superstition was, as I came out, I would jump with two feet and touch the crossbar, then left foot, right foot, touch the crossbar ...

photo by Getty Images

photo by Getty ImagesDid anything bad ever happen when you didn’t perform it?

Oh plenty [laughs]! But superstitions are only as powerful as the mind makes them.

The stuff you went through in your career is well-known. Was there a point that you reached when you came to terms with talking about it?

Yeah, pretty much. It’s never that I didn’t want to talk. Put aside the drugs, the situation I was in was quite perilous, and I had to deal with that first. And you don’t want people around you ‒ people who you have known all your life ‒ involved in that kind of thing. And other than that, I pushed everybody away. When I was going through what I went through, I was very down, a very angry person, and I didn’t feel there was a need for people to see me in that manner; I didn’t think it would do anyone any good ... I wasn’t harming anyone, I was harming myself, and I wanted to deal with it in that way. As long as I wasn’t a harm to society, I thought it was no one else’s business, and that includes my family as well; they were really upset about it at the time. I think they got the message that I got myself into it, I needed to get myself out of it. And the refreshing thing was, I can’t think of one person, when I did get myself out of it, who didn’t want to know me anymore. The best thing was coming back to Australia. With hindsight, I probably should have done that earlier, come back straight away, I’m sorry, blah blah blah. Because this is the best environment for me, for personal health. So that’s one regret ‒ that would’ve originally happened in 2002; I would’ve copped some flak, that’s understandable, that I hid for a period of time rather than doing that straight away.

Looking back on it, how much of it had to do with being in England, and its hothouse mix of soccer and celebrity? Would it have been different, say, if you had taken the chance to go to Italy?

Yeah, could’ve been. There are certain things you can’t keep away from the press in any country, and the thing was in England – and this has always been my attitude, this is why I’ve never really complained about anything – when it’s all going well, and you have that celebrity phase, and you’re on fantastic money, you never hear anyone complain. I certainly didn’t ...

When it goes pear-shaped, and they report on that, I don’t think you’ve got a right, unless there’s something untoward which sometimes happens, to turn around and play poor, little rich boy. You’ve got to go with the good and the bad. England is a very special environment in the way they treat their footballers. In the rest of the world, they are superstars as well, in Spain or Italy, but the element of the personal life is a little more intense in England.

I loved my time there and I will return there one day. I wouldn’t be sitting here and talking to you today if it wasn’t for what England did for me. I’ll always be appreciative of that. It was unfortunate what happened; there will be a little bit more to that in the future, I can’t speak of everything about it right now. But a few things have come out which sort of confirmed my suspicions at the time, but if I’d spoken about them, people would go, “What’s he on about, anyway? We don’t believe a word he’s saying because he’s all over the shop.”

photo by Getty Images

photo by Getty ImagesTelevision – is it something that you anticipated you’d be doing?

No ‒ I anticipated I would still be playing now. Unfortunately, that stopped right in the middle. During those years I was off the radar, I didn’t anticipate anything but the next hour. When I came back to Australia, I played for Central Coast for those seven games. During that time, an executive producer at Fox asked me if I would come and work on the Premier League and a Socceroos game. I said I’d love to. Worked on it, asked if I would like to do it full-time. I really didn’t realise until I started commentating how much I actually missed the sport. And the bottom line is, I had the seven games back, I was out six years, and I was never going to play at the level I was used to.

I also realise how much work is entailed. It’s a different kind of pressure. We can talk here like this, but all of a sudden, somebody goes, “Lights, camera, action ... now you’ve got to say this ... ” That’s a different sort of pressure in itself. I never thought I’d face more pressure than going out and playing in front of 50,000 people and not making a mistake. This is the same pressure in a different way.

You can feel it, especially when you talk about something that’s very important. You talk about sanitising and so forth, and when you are on TV and representing your company, you have to be careful with certain things. There are a lot of people out there with different sensitivities, and I’ve learnt that in the past. Like Oscar Wilde says, assume many things, but never assume people have the same sense of humour.

Has being on TV changed your perspective on things? Like when you look at what Mario Balotelli’s done recently, do you have sympathy from being an ex-player, or do you look at the game as a pundit?

That’s a great question. There are times when you fall into the easy way out of destroying something or criticising it. This table would’ve taken weeks to build ‒ we could smash it in one second. Sometimes players do things that do piss you off. It’s really important to remember back to when you were a player, and that some things are not black and white; some are grey. When somebody does something particular, yes, but from my perspective, I’ve got to be careful not to be a hypocrite.

It’s important to think to yourself, “If I was in that position, would I have acted any different?” I’m very fortunate, without trying to sound conceited, that I played and succeeded at the highest level. The fact is, I pretty much stopped at my peak – I didn’t have any down time. I can only go off that ... you never know, the guy may be on the brink of having a divorce, his kid may be ill. So you’ve got to try to put yourself in that position, especially with mistakes off the pitch. On the pitch, there’s an excuse for anything but not trying. I don’t think professional sport is not trying. There are levels of desire, but when you see that, that’s one thing you have to stamp on.

photo by Getty Images

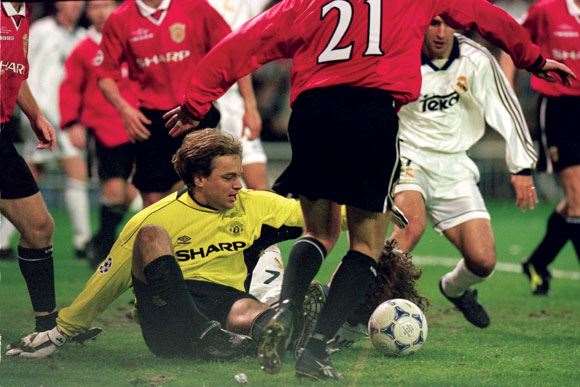

photo by Getty ImagesWhen you returned to Man U in ’99, the club was at one of its historic highs, coming off the treble, you’re replacing Peter Schmeichel – was there a “holy shit” moment?

Not really, because it was in the pipeline. I’d prepared myself for that idea. The club had changed a lot obviously, because when I was there when I was 19, they still hadn’t claimed the Holy Grail of a Premier League title, which they’d last won in the late ’60s. I knew the majority of the boys in the dressing room from before, when they were young kids – Dwight [Yorke] was there. I didn’t think “holy shit”, but I realised the expectations I had to live up to because of my predecessor. If you look back at that season, we won the title by 18 points, we won the World Club Championship, the first time a British team had done that. The disappointing thing for me was, I had one of my best games in a quarter-final first leg against Real Madrid when we drew nil-nil at the Bernabeu. In between that and the second leg, I was injured. I got injured three times. The other problem was, one of the pluses of being there before worked against me in terms of my falling out with Sir Alex over a certain subject. Looking back, regardless if I was right or wrong, I probably should’ve just said, “Okay.” But that’s when you’re young and a bit pig-headed; you just don’t realise that the boss is the boss and you’ve got to go with it.

I find you’re one of the more astute Ferguson observers out there, like the self-indulgent jibe about his birthday earlier this year. How do you see the club transitioning to the post-Ferguson era?

No one is bigger than the club, and he’ll be the first to admit that publicly. But I think privately, it might be a bit of an elephant in the room. He has become as big as the club in terms of its association; where he’s taken the club from when he took over to the multinational conglomerate it is now.

The self-indulgent thing, that was more knowing him. If that was one of his players, he’d have been off the roof. They were losing games at that stage, they’d lost to Newcastle, to Blackburn, they’d just went out of Europe. And there was a choir singing happy birthday. We know his value. He should know his value. There’s still a title to win. I doubt it would’ve happened with any other manager in the world.

The biggest danger they’ll have is that Sir Alex will offer massive input into his replacement, and he’s stated that when he retires, he’ll have some involvement with the club, which he should ‒ he’s earned the right. When the late Sir Matt Busby had finished up and he was hanging around the club following the present managers, it was like there was a ghost, a weight around their feet. That’s what he’s got to be careful of.

This Champions League season, the drumbeat has picked up for Messi as best ever. You played in a high-talent era, Zidane, Ronaldo, etc – how does Messi rate?

As good as anyone. I don’t think you have to play and win a World Cup to prove yourself anymore. The biggest competition is the Champions League now; I think it’s surpassed the World Cup, and I’ll tell you why. The best players are always in there, it doesn’t matter where you’re born. If you’re born in Ivory Coast, you have to play for Ivory Coast. Ryan Giggs, one of the greatest players in the last 20 years, wasn’t able to play in the World Cup. Okay, Champions League, best players in the world, year in, year out, continually evolving, everyone on an even keel. Being born in a certain country can limit what you can do.

Euro 2012, these competitions have a way of ordering the hierarchy in the game. Who do you think is the best goalie?

You don’t win nothing without a great goalkeeper. Gianluigi Buffon has come back from a serious back injury and he’s playing really well. At his best, he’s as good, if not better, than anyone. Petr Cech, outstanding goalkeeper, again had his problems, a lot of his problems had to do with the knock he got on his head in that game against Reading. Manuel Neuer, look, he was excellent with Schalke, but it’s another thing to be excellent with Bayern. I’ve seen him make some good saves with Bayern, I’ve seen him make mistakes. I’d like to see him now in the major tournaments. Iker Casillas has been ever-present, as good as anyone on his day ... And never underestimate that someone can come out of the blue, like Tim Cole from Newcastle. He’s outstanding.

On the subject of internationals, Socceroos vs Iran in 1997 was once a subject too difficult for you to talk about. Still the case?

Not really. My take was the same then as it is now. We got to the top of the mountain, and people got nosebleeds. As players, we have to take responsibility for it. It was in our hands and we let it slip. It was a hard lesson to learn, but it was a lesson that was learned. As a country, a lot of the boys who were involved that night really used that experience when it came to 2006, and that’s the most important thing.

Twenty minutes to go, I think a lot of people started playing the clock instead of playing the game. Thought they were there, conceded one, then went to pieces. That’s what happens in football if you don’t see things through, as in life.

‒ Jeff Centenera

Related Articles

Champion A-League coach set to join Premier League giants

Emerging Socceroos star set to sign for MLS club