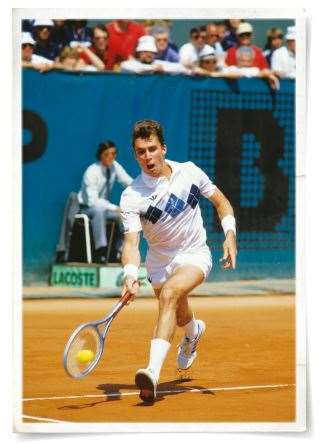

The composite racquet’s arrival ushered in a new era of power and fitness. Its driver was Czech cyborg Ivan Lendl.

The composite racquet’s arrival ushered in a new era of power and fitness. Its driver was Czech cyborg Ivan Lendl.

The composite racquet’s arrival ushered in a new era of power and fitness. Its driver was Czech cyborg Ivan Lendl.

n the 1970s, the “power baseline” game first came to prominence, mainly via Jimmy Connors, as a counter to the kingpins of the serve-and-volley game. Connors was an unusual sight, whomping away in his dramatic “shootout” style, complete with double-handed backhand.

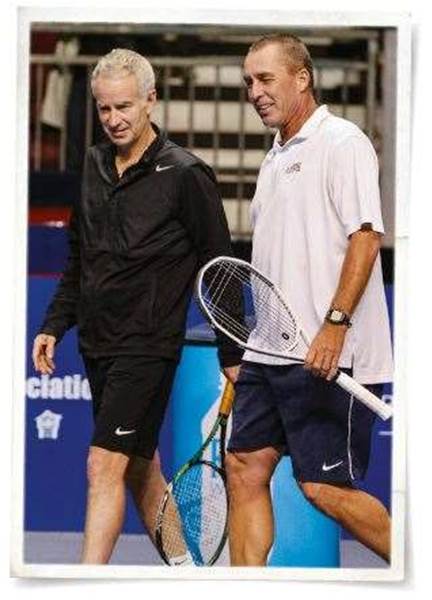

By the end of that decade, the more aggressive baseliner was a lot more common, but before 1975, three of the Opens (Australian, Wimbledon and the US) were still played on fast grass, and the chip-and-chargers, the serve-and-vollyers, still got a look in. John McEnroe came to dominate, and the tradition of exciting exponents like Budge, Laver, Gonzales, Newcombe and Rosewall, King, Navratilova and Goolagong-Cawley, was still alive.

Then the wooden racquet went the way of the dodo, giving way to a composite model.

This ushered in a new era of power and fitness, embodied in one man: the frighteningly efficient Czech, Ivan Lendl.

Whereas Connors’ rifle groundstrokes were flat, passing low over the net, this new breed, with his new weapon, could impart powerful topspin, thus changing the tactics – the very angles – of the game, and turn a defensive style into an attacking one. It was a revolution.

The physics and the physiology of the top-level player began to alter. Bigger men who relied on power were about to take over.

The expressionless Lendl was subject to the same criticism all eastern-European sportspeople get – almost to the point of racial stereotyping. He was robotic, drearily consistent, patient to the point of tedium. But be was also brutal – as heavy-handed as Wladimir Klitschko. Lendl let the ball do the talking – and could he make it talk!

He played a game no one had seen before. Far from being a well-coached cyborg, Lendl was a great tennis thinker. He was the first to construct an entire strategy around the new technology. The composite racquet was capable of doing things wielders of the old wooden variety couldn’t conceive. Not everyone liked the

change. It seemed to mark the death of the pure, talented player of tennis. To see Lendl camping on the baseline, wanging away, aspiring to win every point from there, was to watch the game turn into something else entirely.

But Lendl was damned good at it. He might not be considered the greatest, but with the new racquet, on the new surfaces, he was close to unbeatable at times. His ability to pull off pacey topspin-enhanced passing shots, his introduction of brand-new, radical angles from the baseline thanks to vicious dip, made him the real pioneer.

In 1984, after attaining number-one status, he won his first Grand Slam title, toppling McEnroe at the French. We witnessed the geometry and the physics of tennis change before our eyes. Previously, if a player wanted to open up angles, the accepted wisdom had been to approach the net, as McEnroe did. The closer he got, the more angles were available. The commanding topspin of Lendl’s groundstrokes changed all that. No longer was the game of those beloved old champions necessary, or even practical. Lendl could stay back and still have opponents as good as McEnroe floundering all over the court.

In 1984, after attaining number-one status, he won his first Grand Slam title, toppling McEnroe at the French. We witnessed the geometry and the physics of tennis change before our eyes. Previously, if a player wanted to open up angles, the accepted wisdom had been to approach the net, as McEnroe did. The closer he got, the more angles were available. The commanding topspin of Lendl’s groundstrokes changed all that. No longer was the game of those beloved old champions necessary, or even practical. Lendl could stay back and still have opponents as good as McEnroe floundering all over the court.

On the now-predominant slower courts, big Ivan was the first virtuoso of power tennis. He could generate the sort of force to make it work. Tennis talent alone would now never be enough. Strength, durability and fitness were here to stay.

Serve-and-volley is still alive, as Federer has demonstrated. But the features of the power baseline strategy, like enhanced defence in many modern team games, have been woven into the very fabric of tennis.

Venomous topspin has given rise to an extraordinary breed of player who can impart it and counter it. Players have adapted and now play an all-court game, of which Federer is the supreme example.

But there are also times, today, when we can see entire tournament finals played without one serve-and-volley point.

Today, the groundstroke, launched at incredible speed, is a common sight. We see those astou-nding angles. We see players hitting winners on approach shots more than ever; a volley is rarely required as a coup de grace. The return of serve is now an art form, and an important feature of the power baseliner’s play. Players will still volley, but they’ve had to learn to be more judicious, as topspin mechanics has added a new element

of uncertainty. The increasing power of groundstrokes and passing shots has altered attacking and counterattacking strategies.Later in his career, Lendl further evolved his game in an attempt to win on faster surfaces.

As Wimbledon continued to elude him, he began to approach the net more frequently. At times he looked awkward, but he fared better at the All England with each passing year, and was a finalist in 1986-7. He won eight career Grand Slams.

Courier and Agassi were inheritors of Lendl’s game, and there have been many since, including Fed’s nemesis, Nadal. They were inevitable, given the way technology was headed. But they have Lendl to thank for kicking down the door.

‒ Robert Drane

photos by Getty Images

Related Articles

Champion A-League coach set to join Premier League giants

Split decision: Popovic in mix as Hajduk hunt new boss