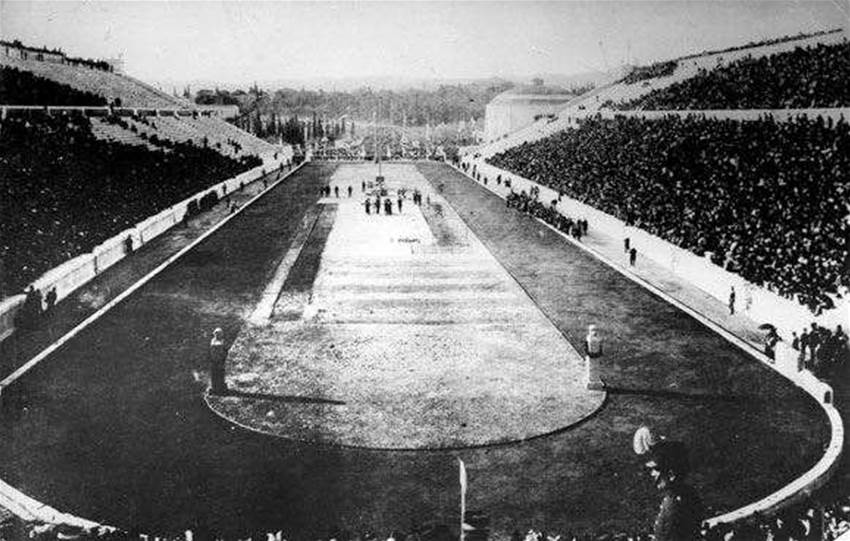

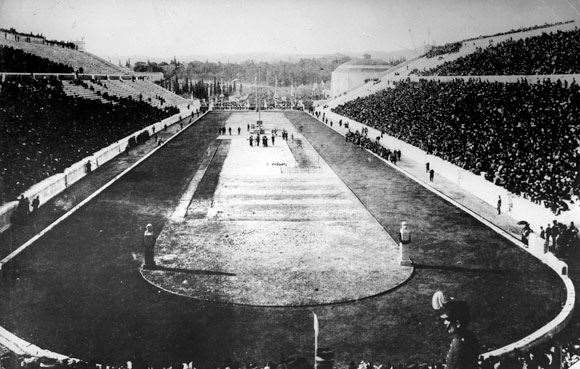

De Coubertin had achieved his dream: once every four years, sports of all sorts coming together for the greatest show on Earth.

Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty ImagesDe Coubertin had achieved his dream: once every four years, sports of all sorts coming together for the greatest show on Earth.

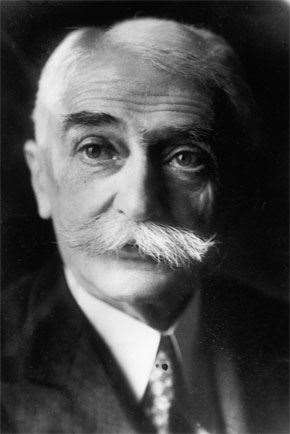

Born into an aristocratic French family on New Year’s Day 1863, product of a rigorous Jesuit education, Pierre de Fredy, Baron de Coubertin became one of France’s leading intellectuals, expounding on education, history, sociology and literature.

Education was his first love, and at 20, he visited England and fell under the spell of “muscular Christianity”, exemplified by the Rugby school, whose revolutionary sports program was instituted by its principal, the great reformer Thomas Arnold. De Coubertin was taken by the notion of the primacy of athletic pursuits in the building of character – a concept Arnold believed should be fundamental to educational philosophy. But even more important to de Coubertin was the link made by the Ancient Greeks between sport and social cohesion – a basic (many might say misguided) tenet of the Olympic movement.

Vital to de Coubertin‘s philosophy was the example of the Athenian gymnasium – an academy that, he believed, perfectly combined physical and intellectual pursuits which were, to his mind, not merely complementary, but inseparable.

As with the birth of many movements, the details are obscure, the chain of events unclear, and the machinations murky. We do know, for instance, that the Olympics could just as easily have been named the Pythian, Isthmian or Nemean Games, as those three events were contemporaneous with the Games at Olympia. It was, in fact, another Englishman who used the term “Olympian”, before de Coubertin was born. William Penny Brookes’ “meetings of the Olympian class” were elite competitions held in the Shropshire region. From there he created a National Olympian Association. He later lobbied the Greek government to restore an international Games to Olympia. In 1866, Brookes organised Britain’s own “national” Olympic Games.

While Brookes’ attempts to internationalise the Games came to naught, so did de Coubertin‘s mission to instil French schools with Arnold’s ideals. Athletics were considered the stuff of inferior education in France. Unshakeable in his belief that sport should be a cornerstone of civilised society, de Coubertin came up with the idea of a congress of international movers and shakers in the athletic world.

There are many arguments that the role of Brookes in the formation of the modern Olympics has been underestimated, and it probably has. But the philosophical power and coherence of de Coubertin’s argument for a modern, international competition based on Olympian ideals is probably what inspired the decision makers.

De Coubertin firmly centred his Olympic notion on ideals of peace, amateurism (although even he wasn’t totally sold on this “ideal” to the extent that some of his officious successors were), and the belief that the struggle to succeed is more important than victory.

De Coubertin’s political skill came to the fore at a time when the athletics world was little more than a loose collection of self-interested groups. In 1892, his first public speech advocating a modern Olympics was met with polite enthusiasm, and not much commitment. In the run-up to his 1894 Congress at the Sorbonne, he decided on the Trojan Horse method, disguising his intentions. Rather than having the revival of the Games as his agenda, he advertised it as a conference about the state of amateurism – an imperilled ideal in the face of gambling and sponsor influence. When they arrived, participants were divided into two commissions, one to examine the state of amateur sport, the other to oversee the revival of the Olympic Games. It was a clever move, and soon led to the birth of the International Olympic Committee. De Coubertin was now backed by the head of Britain’s Amateur Athletic Association and influential Greek and American administrators.

The Games would be held every four years, would consist of modern (rather than the original) sports, and the first Games would be held in Greece in 1896, the second in Paris in 1900. The commission on amateurism came up with the idea of heats to narrow fields for Olympic competition, and on the banning of prize money.

The first Games were a shambles. The football was cancelled when teams didn’t turn up, and the Greeks decided, against de Coubertin’s will, to exclude sports like boxing and polo. The Paris Games were similar, but by this time, de Coubertin had taken over as IOC president. Both the 1900 and 1904 Games were overshadowed by World Fairs. It was, in fact, the intercalated 1906 Games in Athens, inserted to “re-set” the Olympic spirit, that saved the movement. Opening and closing ceremonies, the raising of national flags, the shorter, crisper format, and the registration of athletes through their own national Olympic Committees were all innovations. The influence of the 1906 Games has been played down because of the emphasis on the four-year Summer Olympic cycle.

De Coubertin remained IOC president until after the second Paris Games in 1924, which proved much more successful than the first. By then, the Games had fired the popular imagination, and de Coubertin had achieved his dream: once every four years, sports of all sorts coming together for the greatest show on Earth.

Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images‒ Robert Drane

Related Articles

Champion A-League coach set to join Premier League giants

Emerging Socceroos star set to sign for MLS club